The EU’s latest salvo against the automotive industry to mitigate against climate change is the most radical yet, tightening emission targets more than previously announced and setting a timetable to eliminate combustion engines – all of which will ultimately transform automotive manufacturing and supply chain

The automotive industry’s challenges are stacking up. The immediate obstacles are the recovery phase out of the Covid pandemic, compounded by semiconductor and materials shortages. Those issues have been further aggravated by production slowdowns because of labour constraints, including staff that need to self isolate because of coming into potential contact with the virus (so-called ‘pinged’ staff, as has been the case in the UK).

However, once these relatively short-term issues are eased, the latest announcement from the EU on the roadmap for reducing emissions will be of far greater significance, as it will completely transform the automotive industry within the next decade or so – including the aim to eliminate pure combustion engine vehicles by 2035.

On July 14, 2021, the European Commission announced new proposed legislation entitled Fit for 55, referring to a legally binding (and much tighter) 55% reduction in CO2 emissions (from 1990 levels) across all industry sectors by 2030. This interim target is part of the 2030 Climate Target Plan and the broader objective of the European Green Deal; it is one of the most ambitious interim targets globally on the roadmap to achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 to mitigate against climate change and limit global warming to 1.5°C as per the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement.

What does this mean for the automotive industry?

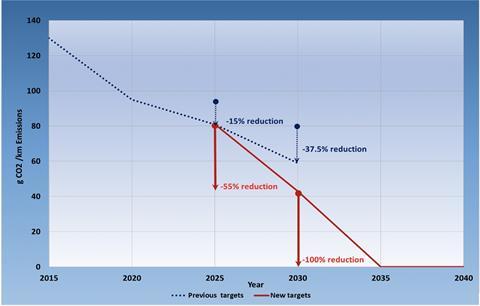

The EU proposal explicitly sets out new vehicle emissions targets, which are significantly tighter than previous targets (see tables below). In short, this will significantly speed up the transition to producing and selling electric vehicles.

OEMs had to meet an industry average of 95g CO2/km in 2020 and 2021 for new vehicles sold. Each OEM had an individual target based upon the group average vehicle weight.

However, 2020 was a phase-in year, with OEMs permitted to exempt the top 5% most polluting cars from the OEM groups overall emissions. Any exceeding of individual targets would be fined €95 ($112) for every 1g of CO2/km over the target, multiplied by the group’s sales that year.

In 2020 it appears that most OEMs achieved their individual emissions targets. This was in part because a much greater number of electric vehicles (EVs) and plug-in EVs (PHEVs) were brought on to the market, while further incentives in the wake of the Covid pandemic helped accelerate a sharp pivot to EV and PHEV sales. Nonetheless, VW missed its target by just 0.5g CO2/km but will have to pay fines calculated to be €115m because of the large volumes. And Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) exceeded its target by a larger 2g CO2/km, but because of its much lower sale volumes, the fines are only estimated at €12.6m. Some OEMs, such as FCA (prior to its merger with PSA to form Stellantis) pooled its sales together with Tesla to avoid fines.

However, for 2021, the 95g/CO2/km target will be harder to meet because it will now be implemented fully with all new vehicles sold counting towards the targets. Thus far, it seems most OEM groups will meet or get close to their individual targets, but this is an even tougher target and relies upon the continuing momentum in EV/PHEV sales.

Aligning future targets

The 2020/2021 targets were merely one hurdle to reach in the journey to full electrification. Many European countries, and OEMs including Ford, Volvo Cars and Renault, could already see the writing on the wall and had already set out their self-imposed plans to phase out or even ban internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles ranging from 2025 to 2040.

However, the array of different mandates and plans across the European bloc could cause confusion and market distortions and actually undermine the overall objective. Therefore, part of the EU’s strategy is to set overarching emissions targets which would overrule national targets, but also to an extent harmonise and align European countries. While the UK would not be part of this alignment because of Brexit, the UK’s target is to ban ICE by 2035 is actually already very closely aligned with the EU.

The roadmap has been redrawn

Part of the unwritten agreement between the EU and the automotive industry for the previous 2020, 2025 and 2030 emissions targets included the industry’s ability to confidently plan, adapt, and invest with certainty by setting out the roadmap a decade or more ahead. But that previous roadmap has now been torn up. Could these new EU emissions targets be accelerated yet again if other industries don’t pull their weight or if we get runaway climate change?

It is understandable why the EU has decided to accelerate emissions targets – especially in line with climate policies passed in the European parliament – but nonetheless could be viewed as a breach of trust on previous targets. At least some in the automotive industry must be reeling at the new targets and the sudden introduction of an ‘ICE ban’ by 2035.

In reality, talk about ICE bans or allowing certain types of hybrids and not others, it is important to understand that the EU is actually not being prescriptive about which powertrain types will be allowed or disallowed. Rather the EU proposal is technology-neutral and is effectively just saying each OEM needs to meet its fleet average emissions targets, with whatever mix of powertrain technologies available – as long as those emissions targets are met.

How EU emission targets will change (2020-2035)

| Year | 2020 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 |

|

Target for cars |

95g CO2/km) |

-15% (81g CO2/km) |

-55% (43g CO2/km) |

-100% (0g CO2/km) |

|

Target for vans |

147g CO2/km) |

-15% (125g CO2/km) |

-50% (74g CO2/km) |

-100% (0g CO2/km) |

|

Comments |

Cars and vans have separate fleet average targets |

Unchanged from previous targets |

A tightening of the previous -37.5% reduction for new cars (-31% for new vans) |

The -100% reduction for 2035 effectively bans ICE petrol & diesel cars by 2035, |

Source: Automotive from Ultima Media

So how will 2030 look?

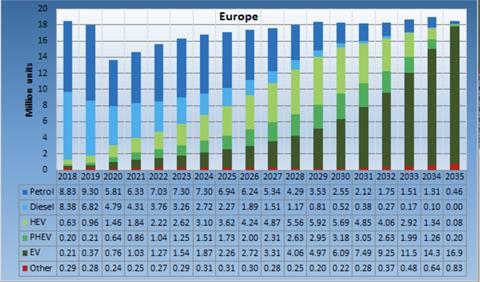

In just under a decade, the product mix in Europe will substantially change. The 2030 goal, where the CO2 target is for a -55% reduction, equates to 43g CO2/km. Our calculations at Automotive from Ultima Media reveal that this would require a vehicle sales mix of 50% EVs and PHEVs (with a tiny proportion of fuel cell vehicles – FCVs), 30% ‘full’ hybrids, and no more than 20% pure ICE petrol and diesel. That compares to 2020, when EVs and PHEVs represented 10% of the market.

While the EV and PHEV share is growing significantly, that is quite a transformation in just 8.5 years away; for automotive model development and production, that is fewer than two product cycles, which typically take 3-5 years.

By 2035 the 100% reduction equates to 0g CO2/km. So whilst the EU has not explicitly banned ICE powertrains, it is technically impossible to build a zero-emission ICE vehicle. This effectively bans all types of ICE powertrains, including all shades of hybridisation, by 2035. Based on the current trajectory of technology, that would suggest all vehicles sold will be full EVs, with a small percentage of FCVs (most likely to be mostly applicable to medium and large commercial vehicles where it is more viable).

Will the Fit For 55 proposal become law?

Of course, the EU legislation is just a proposal and Fit for 55 needs to be ratified by the 27 EU members and European Parliament in November 2021; it may be subject to compromises. Intense auto lobbying, especially from the German OEMs who rely heavily on ICE vehicles for profitability, could result in some watering down of the proposals.

However, this unlikely to happen for various reasons. The escalating climate crisis, as laid bare in the latest report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and the EU bloc’s commitments and wider objective towards carbon neutrality by 2050, are so fundamental that they are highly unlikely to move on this key strategy.

But there is a also a practical reason why the EU is unlikely to budge on emissions targets. The average age of a vehicle in the EU parc is 11 years and vehicles can remain on roads for up to 15 years or more. Therefore, the EU has little choice but to force OEMs to sell only zero-emission vehicles from 2035 onwards so that by 2050 real world transport emissions are virtually zero.

OEMs may look further to pool fleets to reduce how CO2 emissions are calculated. It would appear that a new, separate Emissions Trading System (ETS) will be implemented for transport. Within that, automotive CO2 pools can trade zero-emissions credits. For example, VW with SAIC/MG, FCA (now Stellantis) with Tesla and Honda, Ford and Volvo, Toyota and Mazda, and Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi already operate such pools.

If there are likely to be any concessions from the EU, then it is much more likely to give extra ground on these kinds of support mechanisms than on watering down the headline emissions targets. For example, to address the potential impacts on poorer EU countries and individuals of the new ETS, the EU has the Social Climate Fund, which allocates €72.2 billion (across all sectors) from 2025-2032, which can provide social compensation for low-income countries and individuals, including incentives for EVs and investments in charging infrastructure.

The pivot to electrification requires a commensurate charging infrastructure to achieve the massive industry and consumer transformation needed. The EU recognises the scale of the challenge and the Fit for 55 proposal commits to funding EV charging points every 60km of highway and hydrogen refuelling points every 150km of highway. Whether this is anything like enough is debatable, and considerable investment is likely to be still needed by a mixture of national governments in public charging points, grants for home charging points and private-sector charging point providers.

The EU proposal also sets out how the current derogations/exemptions for smaller manufacturers producing fewer than 10,000 cars or 22,000 vans are likely to be removed from 2030 onwards, making CO2 pooling more necessary for these smaller OEMs. However, there is still a possibility that manufacturers producing below 1,000 units per year may still be exempted; even then, the low volumes involved would have a negligible effect upon overall EU bloc transport emissions by 2050.

Barriers to electrification

Despite this seemingly inevitable march towards electrification, a seamless transition to EVs is not a certainty and there are multiple challenges for OEMs, governments and consumers.

The rapid pace of change could result in demand for lithium batteries outstripping supply. Raw materials could become so scarce that they could push up the price of batteries and EVs.

The charging infrastructure rollout may struggle to keep pace with EV growth, while electrical national grids could struggle to cope with the extra demand.

From a consumer perspective, many drivers may look to hold onto their ICE vehicle for as long as possible, even beyond 2050, without further tax and cost penalties. Governments are also likely to need to review the whole system of fuel taxation, including increasing taxes and road charging on EVs, to avoid losing billions in revenue.

Commercial vehicles are a further complexity on the path to zero emission transport. Battery technology is less viable for large electric commercial vehicles, and may not develop at a pace to meet the 2035 targets. Hydrogen fuel cell may be the only option for heavy commercial vehicles, however hydrogen refuelling infrastructure (despite the EU pledge) remains a major challenge.

Impacts across the supply chain

So how will the legislation affect the automotive industry?

The tightening of the emissions targets will further accelerate electrification and transformation, radically influencing product launches, investment decisions and overall strategy. OEMs will need to completely change their product lines, supply chains, business models, and all within two or three product cycles. This rate of transformation is unparalleled in almost any other industry sector.

Let’s not forget that the pace of electrification is also strong in China. And even the US is looking to catch up as Joe Biden’s aim (a stark reversal of the previous administration’s policies) is for 50% of sales to be EV by 2030, which aligns with Europe’s targets.

This change will be felt across the supply chain and in manufacturing. EVs themselves have many fewer parts than ICE vehicles, and in theory, at least, offer simplified supply chains and assembly once OEMs are producing only electric vehicles. However, during the transitional period of 2021 to 2035, there will be a multitude of powertrain technologies ranging from mild to full hybrid, plug-in hybrid, full EVs and even the development of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles. That means not only complexity for consumers in choosing powertrain types, but this plethora of powertrains multiplies complexity in supply chains and production processes, with the array of different variants often assembled on the same production lines.

Electric vehicles require completely different powertrain components, which means a new value chain and ecosystem will emerge in place of legacy ICE production. These new battery supply chains will have to be developed on an epic scale, and because batteries are cumbersome and costly to transport, localised supply chains will have to be created in Europe to make it viable at scale.

Upstream there will need to be massive investment in EU extraction and processing of the necessary raw materials and battery components. Continent-wide gigafactories with capacity totalling more than 1.5 TWh will be necessary by 2030, requiring massive capital expenditure. And then there are the thermal management systems, battery casings, and the traction power motor and electronics, which the tier suppliers will need to ramp up to much higher volumes. There are particular opportunities in the software that monitors, regulates, controls and optimises the battery charging/discharging – as significant performance advantages can be made there.

Much of this new electrified world order will be highly disruptive. It will mean a new set of companies jostling for position in this lucrative emerging new value chain. Battery cell companies, such as LG Energy Solution, CATL, Panasonic, SKI et al, are likely to wield greater power in the automotive value chain increasingly. As a result, a range of new partnerships, joint ventures and alliances will form between battery cell companies and OEMs to leverage their symbiotic competencies.

OEMs will feel the pinch, but there are positive

OEMs are between a rock and a hard place. They either invest intensely in R&D, pivoting to hybrids and EVs, requiring new product lines, and capex on new assembly lines, or they incur the wrath of punitive EU fines for not meeting the emission targets in 2025, 2030 and beyond. Ultimately, this will mean lean times ahead and investors would be justified in downgrading their auto stock portfolios as it is going to be a financially tough decade for the industry.

Despite these challenges, the EU’s plan and roadmap are at least certain and clear, which means there is an overwhelming inevitability to the transition to electrification. The upside is that, despite the industry upheaval, businesses at every point within the extended automotive value chain can plan with certainty that 2035 is going to be electrifying – assuming the EU doesn’t move the goalposts again.

No comments yet