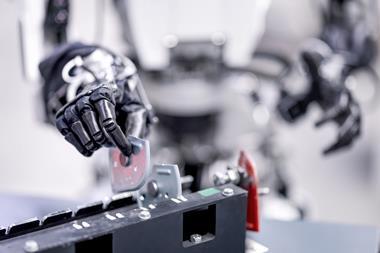

Recent investment at the West Midlands factory has resulted in a new assembly area for JLR components

In terms of numbers alone, the ZF Lemförder plant in Solihull, UK, would not appear to be a major portion of the German-owned ZF Group; ten years after its establishment, it employs just 113 people out of more than 20,500 in the company’s worldwide Car Chassis Technology division, which in turn accounts for less than a third of the 74,000 people in the entire organisation. But in terms of flexibility and quality levels, ZF Solihull holds itself to be at the forefront of global automotive supply chain performance.

The company is the sole supplier of front and rear suspension corner modules to the Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) plant just six miles away in the Solihull area, with a smaller operation providing knuckle assemblies to the vehicle-maker’s slightly more distant Castle Bromwich site. ZF Solihull produces corner units for the Land Rover Discovery, Range Rover and Range Rover Sport, and from August this year it has been operating a new assembly line turning out corner units for the Sport vehicle. The two main assembly areas are located side-by-side on the 3,600 sq.m production floor at Solihull, which also houses a logistics area and the much smaller knuckle assembly operation.

According to Terry Somerfield, managing director for ZF Lemförder UK, who is based at the company’s site in nearby Darlaston, from the middle of 2014 the first line was producing 68 configurations of corner modules for the three vehicles it serves at a rate of 42 sets an hour, over three shifts a day and five days a week, with a defect rate approaching zero parts per million. It was doing so, moreover, in a production environment well beyond mere batch assembly or even just-in-time delivery schedules. The underlying philosophy at ZF Solihull is that of just-in-sequence manufacturing, which effectively means being able to assemble the units – or to be more precise the specific set of four units that each vehicle requires – in a batch of one if necessary and despatch them to JLR both on time and in the sequence they were ordered.

ZF Solihull necessarily sits at the centre of its own logistical network that extends out as far as eastern Europe. The operation has 26 suppliers in total: 14 in the UK, with one of those being another ZF site, and 12 elsewhere in Europe, with two of that number also being ZF locations. Buffer stocks of parts kept at Solihull are lean but also indicate a pragmatic attitude towards safeguarding the operation against possible disruptions caused by unforeseen events. Somerfield reports that stocks of parts kept on site from UK sources are sufficient to support a further one to two days of production, while the corresponding figure for those from non-UK sources is three to five days.

A recent ramp-up

Initially steady growth at ZF Solihull has been ramped up quite sharply in recent times. When the plant was founded in 2004, it employed 43 people and represented an investment of around £6.5m ($10.2m). Over the last couple of years, roughly the same amount of money again has been spent to support a move from two to three shifts a day on the old line, in 2012, but more importantly to install the new assembly line, which started out manufacturing 20 sets of Sport corner units per hour, in 32 variants, on a single shift basis. The purpose of the new line is not only to allow for an increase in the output of Sport corner units but also to free up capacity on the older line to enable an increase in the output of Discovery and Range Rover units.

In terms of the infrastructure, the two main assembly areas are also constructed according to common underlying principles. As Chell confirms, both have a mixture of manual and automated assembly stations with in-line and consistently automated quality control checks at each successive stage so that they achieve a target of “no fault forward”. The business requirement for that is easily explicable: no further quality control checks are carried out at JLR, so every completed corner unit that leaves the ZF plant must perform to specification. “ZF is totally responsible for the integrity of the parts,” states Chell.

According to Chell, the first assembly area has operated largely unaltered from the first day of production at the plant until 2011, when it underwent significant modifications to accommodate the introduction of the Range Rover and Range Rover Sport vehicles the following year. Nevertheless, the fundamental methodology has remained constant. Manual operations are typically component loading tasks as well as such procedures as the tightening of the easier-to-reach and lower torque fixings, plus the attachment of cabling. Automated methods are used for more awkwardly placed and higher torque fixings but also insertion tasks requiring higher pressure forces, for instance in bush and bearing elements.

Another basic operational principle of the line is that of ensuring complete traceability not just of every unit made but of the quality control checks carried out during assembly. Hence the reliance on automated testing procedures for such factors as brake disc run-out and driveshaft pull-in, with all data recorded for future reference so that each corner unit has what Chell terms “an electronic birth certificate”.

All these procedures must allow for the high degree of product variability involved. A number of factors define a specific variant. The most immediate is simply where it will be located on the finished vehicle – front or rear, left or right. Other contributors include: differences in brake discs and callipers, driveshafts, control arms and knuckles.

Lining up greater reliability

Meanwhile, the new assembly line represents an interesting mix of continuity and further development. Chell says that, although it embodies the same fundamental process steps, it also seeks to build on the experience ZF gained on the old line in several key areas. One of these is disaster recovery and contingency planning. Chell explains that the old line was characterised by shared electronic services, whereas the primary and back-up processes of the new line have separate infrastructures, for instance controllers, so that if one network is turned off completely the other can still operate without compromising the effectiveness of the line.

In addition, the layout has been modified so that there are no automatic assembly stations in between their manual equivalents – a configuration that Chells says makes the line much more flexible and able to cope with changes in customer requirements. The ten manual stations are positioned around the perimeter of the installation while the six automated ones are grouped internally.

According to Chell, ZF regards the new line as representing best practice for this type of assembly operation, across the worldwide organisation. He explains that this is not just because of the lessons learned from its immediate neighbour on the shopfloor at Solihull, but because the new line also complies with ZF’s global standard for assembly line configuration – ‘Flexline’. The objective is to enable maximum flexibility to cope with changing customer demand and it is achieved through maximising the standardisation of both physical and electronic elements, facilitating rapid modifications.

One benefit that ZF has already gleaned from the specification and configuration of the new line is the relative ease with which it has been commissioned. Chell says that its predecessor took some time to reach an acceptable level of operational efficiency, whereas the new one has reached that goal quickly and smoothly, so much so that it is due to ramp up to two shifts a day just three months after it started operations.

New line, new recruits

The aim of the recruitment process was to find out if candidates had the ability to follow a set process as well as the necessary dexterity to carry out some of more intricate tasks they would face while working on the line. Providing these generic criteria were satisfied, says Chell, “we can train them in everything else they need to know, so we didn’t need to constrain ourselves with any more specific requirements.” Although the plant’s location in the heart of the UK automotive industry has meant that some of those brought onboard already had relevant experience, the nature of the line is such that recruits without any background in the industry could quickly get up to speed.

As a result of these recent developments, ZF believes it is now well positioned to cope with future demand. Indeed, Somerfield identifies the planned introduction of the replacement for the Discovery in 2016 as the point when the ZF Solihull plant will be required to step up its own operations; he is confident it will meet the challenge.