Volkswagen has recorded notable growth in Russia over the last few years, but management are being careful not to get excited

Sitting on the Okra river around three hours south of Moscow is the small administrative city of Kaluga. It plays an important role in the Russian automotive industry as home to several vehicle factories operated by foreign manufacturers, the largest of which is a Volkswagen plant.

With an output of 225,000 units a year, VW’s Kaluga facility is home to production of the Tiguan, Polo and Skoda Rapid. The plant opened back in 2007 and started life as a SKD facility. Full-cycle production, including welding and painting, of the Volkswagen Tiguan and Skoda Octavia started two years later, and production of the Polo was introduced in 2010. The Audi Q7 is also assembled from semi-knocked down (SKD) kits.

Construction of the plant’s engine facility started in 2012 and was completed in 2015, while a new bodyshop was opened a year later. According to Oliver Grünberg, technical director and deputy general director of Volkswagen Group Rus, this all came at something of an awkward time.

“The decisions to build the engine production facility and the bodyshop for Tiguan were made long before the crisis,” he recalls. “We had these plans firmly in place, and we decided to stick to them despite the situation in the market.”

New car and light commercial vehicle sales in Russia totalled 2.49m in 2014, according to the Association of European Businesses. That figure plunged by 35.7% in 2015 to 1.6m units, before falling by a further 11% in 2016 and hitting a record low at 1.43m units.

This caused several OEMs to implement streamlining measures, such as cutting jobs and closing manufacturing facilities.

But VW held its ground, despite its deliveries dropping by 38.8%, from 128,100 in 2014 to 78,400 in 2015, and then again in 2016 to 74,200. A total of €250m ($280.23m) was spent on the engine facility, while the bodyshop for Tiguan cost around €180m.

“And during the crisis, which bottomed out in 2016, it was very difficult to make planning decisions for new projects that would be taking shape now,” Grünberg continues. “So at the moment, we are going through a quiet period in terms of new projects. But all the planning decisions that we have made over the past year will soon come to the fore, so we will have a storm of follow up and completely new models being launched. We have six SoPs (starts of production) in 2019, 2020 and 2021, so there is lots to get ready for.”

However, despite the flurry of activity, there won’t be any major changes taking place in terms of the Kaluga plant and how it currently operates. “That’s because the follow up models are based on the platforms of the previous models, so we can reuse a lot of production equipment,” Grünberg explains. “We have also brought the VW Polo and Skoda Rapid far closer together in terms of the manufacturing processes, which has saved a lot of investment.”

Kaluga’s engines

Like many other companies operating in Russia, VW is weary of the market’s volatility. This is one of the main reasons behind minimising investment. The company has also safeguarded its position by exporting engines from Kaluga to other facilities in the VW Group network, including Seat’s plant in Martorell, Spain and the VW factory in Uitenhage, South Africa. Having done so, it is now not entirely reliant on demand coming solely from the Russian market.

VW became the first foreign OEM to start operating its own engine production facility in Russia back in 2015. Built as a 32,000sq.m extension to its Kaluga plant, the facility cost €250m and had an initial annual output of 150,000 units. The company recently announced that the 400,000th engine had been made at Kaluga. This followed on from a record year of production in 2018 at 161,000 units, marking a rise of 56.3% over 2017.

Around 680 engines roll off the production line each day, all of which are the 1.6-litre petrol engine in VW’s EA211 series. They come in two different power outputs – 90 and 110hp – and are installed in 11 different models across the VW Group, including three Russian-made models – the VW Polo, Skoda Rapid and Skoda Octavia.

Little by little

Aside from preparing for the introduction of new models and churning out engines, the team at Kaluga have been busy churning out more units than initially planned. The factory was built to carry out 30.5 jobs per hour but is currently doing far more.

“When we saw demand rising after the crisis, we managed to push to 34 jobs per hour without making any investment,” Grünberg reveals. “Now we are running at 37 jobs per hour, which took a little bit of investment. We will soon go to 39 jobs per hour but plan to keep operating at just two shifts a day with the same number of people working on the line.”

Some technical changes were made in order to achieve this, such as increasing conveyor speeds and condensing work content. “It was a matter of finding small efficiency gains,” Grünberg notes. “Another example is that employees now identify themselves with their company ID card, whereas before they were doing 300 stems in their traveller card. So each job took about 10 seconds less, which is quite small, but when you think about how that all adds up it’s huge.”

Most of the improvements were done through manual processes, but looking forward, digitalisation could play an increasingly important role in aiding production at Kaluga. However, Grünberg does not expect this to be an overnight change. Instead, digital tools are likely to be slowly introduced depending on the benefits they offer.

“Our products aren’t as high-tech as those that are being made at the Bratislava plant, for example,” he says. “Here they make the Q7, new Tourag, and Porsche Cayenne. There is no chance that you can make all these mechanically. But it’s different with the Polo, Rapid and Tiguan, and although these models will get more advanced, they currently require a more traditional production methodology. So at the moment, digitalisation doesn’t play too much of a role.”

Furthermore, the current cost of digital tools is too high when compared to labour costs. Therefore, the likelihood of a sudden and major shift towards digitalisation at Kaluga is slim. “Investing in digitalisation is not cheap,” Grünberg adds. “As wages here in Russia aren’t very high at the moment, it’s not very easy to make a business case for industry 4.0 solutions. And there is a general statement from the VW Group that we don’t do digitalisation for digitalisation’s sake. There must either be a business case or a customer benefit. But honestly speaking, the customer won’t realise if we use pick-to-light systems, or if we have a second check on the car before it goes to the next phase of production.”

Platform professionals

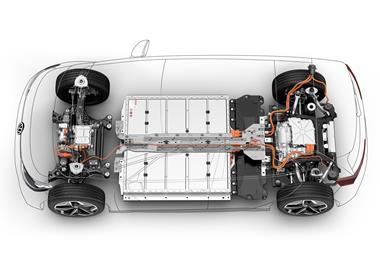

VW is one of many carmakers that have been making a splash in the field of electrification, consistently promising new models for the market and lofty sales targets. Underpinning this strategy is its modular electric toolkit (MEB) – a platform that was designed specifically to reduce the cost of EVs. However, Grünberg suggests that Kaluga would not be using the MEB platform anytime soon, as electrification “doesn’t make sense for Russia due to the driving distances and the cold conditions.” Away from the glitz and glam of the EV market, and VW also has its long-established Modularer Querbaukasten (MQB) platform for vehicles that have a front-engine and front-wheel drive layout. This is the base for over 30 models in the Audi, Seat, Skoda and Volkswagen brands, including the vehicles that are made at Kaluga.

Night and day

Would VW have been better off opting for a different location? The decision to build a plant in Kaluga was taken a long time ago – almost 14 years ago – and at that time, not all areas of Russia were seen as favourable for western investment. “Russia had its military industry as well as its strengths in oil and gas, so the atmosphere of attracting investment was not there in some places,” Grünberg recalls. “But Kaluga was one of the regions that had no oil and gas industry or military.”

There were three politicians, including the local mayor, who decided it would be beneficial for the area to attract western investment. They were able to convince VW Group that Kaluga was the place to be, though there were some issues.

“The logistical connections were questionable ten years ago,” Grünberg remembered. “There were no lights or road markings on the motorway between here and Moscow. And now it’s totally different.”

Topsy turvy conditions

The Russian automotive market made a slight recovery in the two years following the 2016 drop, though figures have fallen again in 2019. AEB statistics show that sales of passenger cars and light commercial vehicles hit 1.8m units in 2018, marking a rise of 12.8% compared to 2017. January 2019 saw the 13th consecutive month of growth, with a small 0.6% increase in sales over the same month in 2018. However, a slump has been recorded between January and June 2019, with sales dipping by 2.4% when compared to the same period in 2018. Expectations for the full year are not looking rosy. “Market expectations for the second half of the year are not fundamentally better,” commented Joerg Schreiber, chairman of the AEB. “It is clear that market growth in the full year of 2019 is not a realistic scenario anymore. Even with a certain trend improvement in the second half, it would appear that the best outcome the market can hope for is to equalise last year’s sales result.”

VW has a test programme at Kaluga for its vehicles, which includes real-world driving. Part of this is for the vehicles to be subjected to poor road conditions. “But we are hardly able to fulfil that anymore,” Grünberg notes. “We basically have to go to remote villages where the infrastructure programmes have not caught up. We also have a rail network and an airport now in Kaluga, so it’s fair to say that the logistical connections now are brilliant in comparison to what they were.”

The company also has an agreement with GAZ Group, which carries out contract manufacturing work at a facility in Nizhny Novgorod, located to the north-east of Moscow. It is currently home to production of the Skoda Kodiaq, Octavia and Yeti, as well as the Volkswagen Jetta.

In 2017, the two companies signed an extension to their manufacturing agreement, ensuring that VW and Skoda models will be made at the facility until at least 2025. Back in 2011, the GAZ Group facility installed new assembly and bodyshops ahead of starting production of the Skoda and VW models. It also upgraded its paintshop and enhanced its logistics and quality control systems.

“The relationship between our Kaluga plant and the facility in Nizhny Novgorod is getting better, but the latter is contract manufacturing while we are doing the complete production business for VW models here at Kaluga,” Grünberg clarifies. “One of the key strategies that both plants share is the build-to-ship idea. So we don’t build up capacity at Kaluga or at the plant in Nizhny Novgorod, which is something we learnt from the previous crisis.”

The main driver of setting up in Nizhny Novgorod, he continues, was VW’s obligation to cooperate with a local manufacturer. When a company from outside Russia establishes manufacturing facilities in the country, they are required to fulfil a number of requirements within a certain timeframe. For VW, one of these was to invest further in its Kaluga factory, which resulted in the construction of the engine facility. “Another was to increase the localisation of parts to 60%, and a third was to cooperate with a Russian company,” Grünberg revealed.

Catering for Russia

Although predicting demand in Russia’s automotive industry is practically impossible, Grünberg is confident the Kaluga plant will continue to have an important place in the VW Group’s production network. In 2018, it received the ‘Transformer of the Year’ award for best performance out of all VW plants across the globe, and for the first time since it started operating, production volume reached 200,000 units.

One of the factors behind this success, he suggests, is its approach to addressing the needs of the market: “The strategic plan here comes in the form of product. We don’t have full-scale western European models stripped down to make sense for the Russian market. We took the opposite approach, using Russian demands as the basis for the models we make here and then speccing up if required.”

No comments yet