Chassis components keep the wheels from falling off the EV revolution. Illya Verpraet found out how Gestamp is managing the change with material and quality control innovation

Headlines about electric vehicles tend to focus on the powertrain – the batteries and the motors. Given that they are the main difference with conventional vehicles, that’s not entirely unfair, but OEMs can’t just stuff 600hp and 500kg of batteries in a car and hope for the best. Suppliers like Gestamp, which makes chassis components such as suspension arms, crash structures and motor and battery mountings, have to be on board as well, not just with a willingness to produce the components, but to also contribute their unique expertise to the design.

According to Tom Larsen, head of advanced technology and application of Gestamp’s chassis department, the changes at Gestamp aren’t momentous, but the requirements of EVs do build on and accelerate some of the existing trends: “Fundamentally for the design of electric vehicles, the chassis performance requirements are consistent [with those] for ICE, plug-in hybrid or battery electric vehicles, and they’re driven around the need for stiffness for vehicle dynamics for strength for durability for the life of the car, and also safety in the event of a crash.”

As well as the available packaging space changing in the absence of an engine, he says that there are three challenges: weight reduction to compensate for the heavy batteries, maintaining comfort by reducing transmission of road noise, and ensuring safety, as there is no engine to take the brunt of a crash.

The need for weight reduction has prompted the search for lightweight materials, but Larsen stresses that what’s essential and what Gestamp is focusing on is design for manufacture. As budgets get stressed in pandemic times, just as important as the functionality of a component is whether it can be manufactured economically.

“One of the ways we do that is through having a network of global R&D centres where we have both our product designers and our manufacturing engineers in the same location,” he explains. “[That way] we can design the product close to our customers, meet their requirements, but also work with our engineering teams to make sure that design for manufacture is accounted for in the design as well. Making sure that the designs can be manufactured is key to delivering the light weight. If you don’t do that you can end up having to add a lot of material and weight to the product to make it manufacturable as well.”

“If you don’t [account for design for manufacture] you can end up having to add a lot of material and weight to the product to make it manufacturable as well” – Tom Larsen, Gestamp

Watch Tom Larsen, head of advanced technology and application of Gestamp’s chassis department in an exclusive panel with experts from ZF, ABB and Henkel focusing on how electrification is transformation production for tier suppliers during the AMS Livestream Hour on March 31, 2021.

Not just steel

Over the last few years, Gestamp has been investing in lightweight materials such as aluminium and hybrid materials, finding that OEMs have been willing to achieve reductions in weight, even at a premium, especially as they scramble to get their EVs commercialised. At the same time, it remains a struggle with some of the volume carmakers Gestamp is dealing with, where steel is still in high demand. Larsen still sees a bright future for steel, as modern cold-formed steels can be made so thin while still retaining ample strength, that corrosion resistance becomes the limiting factor rather than stiffness.

Nevertheless, Gestamp has had to evolve from a business that used steel exclusively to one that innovates with aluminium and hybrid materials. “What we’ve done for our development in the last few years is not constrained ourselves, Larsen explains. “If a customer specifically wants aluminium, be it for marketing or for a genuine belief that it is the best solution, that’s fine, we can deliver it. If we want multi-materials on composites we can look into those products and do that.”

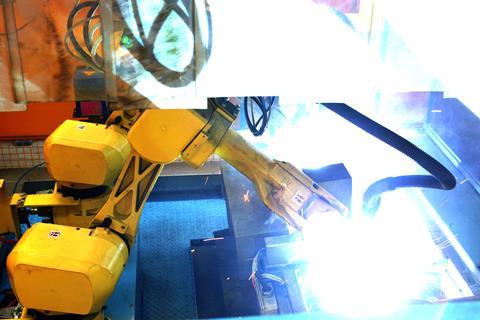

He says Gestamp has done a lot of testing to understand the fatigue behaviour of welds of heat-affected zones, particularly with aluminium, but key to maintaining high quality are the digital certificates, where data is gathered from every step of manufacturing. This allows for every part that is manufactured to be individually tracked and for issues to be identified quickly.

Data, data, data

As many of the components Gestamp produces are not only critical for safety, but also highly complex to manufacture, it needed a robust quality control mechanism. Bernhard Feyo, Industry 4.0 chassis project manager says the answer was to implement Industry 4.0. “For me, it’s all about data. It’s data, data, data,” he says.

A crucial part of this was to make sure that every component can be individually tracked throughout its journey. Gestamp calls it unitary traceability. Instead of testing products in batches, every component gets a ‘digital quality certificate’ that stores every significant process detail in the company’s IoT (internet of things) platform.

Those process details come from everywhere. Feyo explains: “All of our machines and devices that transform our materials into products, they generate data. And all of that data, which can come from sensors, cameras, cylinders, power units or PLCs, we ingest that data, we read it and we evaluate it.”

All of the data, as well as environmental data such as room temperature is then sent to a cloud platform so that it is accessible from anywhere in the world in real time to make instant decisions, so that in case of an issue an operator knows what happened and can make adjustments. At the same time, the data is historized for further analysis to allow for process improvements.

He reckons that having not just data about the quality of the part itself, but about every action that produced that part, is the real innovation, particularly in an environment that needs to cope with huge variety in the parts it produces and the materials and technologies it uses.

All of which leads to the issue that having a lot of data is great, but as panellists from BMW and Ford in the recent livestream about automation agreed, it is possible to have too much of a good thing.

Feyo says: “I think that everybody has that problem and I think also that this is a this is a path, … an ongoing process of learning and improving. [With Big Data] you want to cross reference and do analytics, but first of all you need to organise all of that data: what do you do with it, where do you store it and how do you make sense of it.

“Then you need to be able to benchmark and compare, and then maybe run machine learning that will show you the insights and the clusters of data that you try to look for.” Ultimately, the first step is to start with smaller investigations and add detail over time, he concludes.

It’s one of the challenges that needs to be overcome to realise the ultimate goal of having visibility of every part of every complex process. If you could measure absolutely everything, including the things that we can’t measure yet, it would in theory be possible to predict where issues occur before they are caught in an end-of-line inspection.

“All of our machines and devices that transform our materials into products, they generate data. … We ingest all that data, we read it and we evaluate it.” – Bernhard Feyo, Gestamp

“The major advantage of this is that you are doing it real time,” Feyo explains. “An end-of-line inspection is very nice, but because it’s at the end of the line, you have already added value to this part. If the problem occurred at the start of the process, then you performed ten more operations on it, and in the end you can’t use the part, you’ve lost money and efficiency.”

The end goal is to move from detecting problems to having integrated process control that can allow actions before problems crop up. “That is our vision and our goal. Having all this integration, it’s a new world.”

Development partnership

At the same time, the data is fed back to the design and R&D departments who can use it to design products with manufacturing in mind. “That has been a big investment in R&D time and energy to have that data,” Larsen adds.

He reckons that having that R&D capability has been a real asset in the last few years, as carmakers have tried to rush their first EVs into production and many of them were keen to farm out some of the development work to suppliers like Gestamp. There is still a mix of OEMs who have all the expertise in-house and just employ Gestamp as a build-to-print manufacturer, but he finds it is increasingly important to offer the design-for-manufacture perspective.

“The performance requirements for chassis products regarding vehicle dynamics, durability, safety in a crash, all of those requirements related to the car; customers are very knowledgeable about that and a lot of them can develop products to do that very well, but they’re not familiar with the manufacturing processes, such as forming simulation, welding processes, fixturing, even the sequence of welds and how it can affect heat distortion and other production considerations.”

He says that Gestamp’s engineers, who often started out as apprentices on the shop floor, understand the processes, the materials and the development, which ultimately allows them to effectively pursue lightweighting by avoiding parasitic mass.

“The definition of lightweight is everything doing a job,” he states. “If anything isn’t – if you need a bit of material because you need a draft angle for production to make the part, but it’s not actually needed on the car – that is parasitic mass. I think that is where our designers can support development, where Gestamp can support, is in linking the performance and the manufacturing together, to make it efficient.”

No comments yet