Skoda production chief and VW Group veteran Michael Oeljeklaus sets out the Czech brand’s route map to more EVs and more efficiency in this exclusive interview.

Few people know the Volkswagen Group as well as Michael Oeljeklaus who has held multiple executive roles there over more than 30 years, the last 12 of which have been at Škoda. Oeljeklaus tells AMS sister publication Automobil Produktion about e-mobility and synergies with other VW Group brands in this exclusive interview.

Where is Škoda headed with electrification?

We are accelerating our e-offensive and will be launching three more electric models by 2026. By 2030, the electric share at Škoda in Europe should be 70 percent or more - that’s our plan. We have just adapted our brand identity, with a new design language and a new logo. We have set ourselves a lot of goals.

With the start of VW Group’s MEB battery systems in Mladá Boleslav, is Škoda gaining in prominence in zero emission cars among the group’s brands?

Škoda has become a reliable partner in the Volkswagen Group over the past 30 years. This can be seen above all in the responsibilities we are now taking on. For example, in India, a challenging market, we are also responsible for the MQB 27 platform, which is also used in Brazil and China. That shows people have confidence in us, and this goes for electromobility too.

Could Škoda take on more responsibilities in electrification within the VW group?

With Thomas Schäfer running the Volkswagen Passenger Cars brand and previously head of Škoda, the question of brand groups will certainly become more significant. The volume brand group is made up of Volkswagen Passenger Cars, Volkswagen Commercial Vehicles, Seat/Cupra and Škoda. In this group, we will in future share tasks even more efficiently than before, leverage synergies and take on corresponding responsibilities within the group. This will be a much more integrated approach.

Does this also apply to synergies in logistics and procurement given the strains in these areas now?

I still remember well when the topic of the semiconductor crisis came up. That must have been in December 2020. At first, I thought that this was a typical bottleneck that we had experienced before. I thought it would last a few weeks or at worst, a few months, and then the situation would settle down. But then the number of components that could not be manufactured due to missing chips mushroomed. By this far into 2022, the issue has still not been resolved. We are now seeing some relief though. August was probably the first month in over two years when we were able to run all Škoda plants at full capacity again. Before that, we still had cancellations of production shifts every week. That could arise again quickly. Neither coronavirus nor the semiconductor shortage nor the Ukraine conflict have been resolved. And the next challenge is already looming.

You mean gas supplies?

Exactly. We don’t know what the fourth quarter will look like in terms of gas. Like any automaker, we are extremely dependent on it for production. These four issues add up and present us with enormous imponderables. So on synergies, with regard to chips, we naturally have corresponding distribution hubs in the group and can distribute components centrally to the brands as required. The volume group is not necessarily top priority, but rather the brands with higher earnings contributions. I hope that we will have finally solved at least one of the aforementioned problems by the beginning of 2023.

In Mladá Boleslav, you produce MEB and MQB models on one line. What challenges have you encountered in the process?

Here at our headquarters, we produce the electric Enyaq iV and the Octavia, our volume model, at the Mladá Boleslav I plant on one body shop line, in one paint shop and on one assembly line. The biggest challenge here is the different weights. The body of the Octavia weighs around 450 kilograms - that of the Enyaq around 200 kilograms more. This is mainly due to the rigidity, the structure, but also the protection of the battery. So in a 58-second cycle, our systems are dynamically subjected to very different stresses. To meet this demand, we had to invest heavily in overhauling the factory. I fought hard within the group to ensure that we build this model here at our headquarters in the Czech Republic, and succeeded. We are currently producing around 350 Enyaqs a day. Next year, that figure is set to rise to 500, and from 2024, 800 a day. With the Octavia, I can replenish capacity flexibly. The bottom line is that the factory is always optimally utilised.

Regarding multi-brand plants, can you imagine one or two Seat or Volkswagen models rolling off the production line in Mladá Boleslav in the future?

I can very well imagine that. If you ask a production engineer what his plant should ideally look like, he will tell you that it should be one platform, three powertrains, four colours, then the cycle balancing times would be eliminated. In Mladá Boleslav, however, we produce an internal combustion engine, then an Enyaq, then two Octavias, then a coupe and then five Octavias again. This is where the aforementioned multi-brand projects come into play. If the group wants to run all its plants as close to capacity as possible, such synergies are essential.

Are there also some downsides to that?

In order for these multi-brand projects to function efficiently, we must not focus exclusively on return on sales, but must adjust our targets. Everyone in the group is aware of this and we are working together at full speed to achieve it. I’m a big fan of this multi-brand idea - if the returns are right.

Michael Oeljeklaus has been head of Production and Logistics at Volkswagen’s Czech subsidiary Škoda since 2010. Prior to that, the mechanical engineering graduate held several positions at Volkswagen, including Technical Director at Shanghai Volkswagen, China, (2005-2010), Technical Managing Director of Volkswagen Sachsen (2002-2005) and Head of Start-up Vehicle Projects at the Volkswagen brand (2001-2002).

You have also set yourself ambitious goals in terms of CO2 neutrality at your plants. What is your vision of a climate-neutral factory?

We have long since moved on from the vision stage. Our goal is to manufacture all products, be they vehicles or components, in a CO2-neutral way here in the Czech Republic in the second half of the decade. Vrchlabí, for example, has already been climate-neutral since 2020. The plant, for example, is powered exclusively by green electricity. And in Mladá Boleslav, we are currently working with our service provider Sko-Energo to operate our power plant here completely CO2-neutral with wood chips in the future. We are talking about biomass here. The Czech forests are quite capable of producing it. However, we also need 500,000 tons of it per year.

A modern factory is not only green, but above all smart. Where does Škoda stand in terms of Industry 4.0?

We have been working on this issue for many years. We founded the FabLab specifically for this purpose, in which we are further developing and testing the digitalization of production.

At the moment, our main focus is on drawing the right conclusions from huge mountains of data. In the press shop, for example, thousands of sensors generate thousands of pieces of data every second. Artificial intelligence is now needed to work its way through this flood of information. We can build applications around predictive maintenance on this, for example. If the plant itself can tell us that a rolling bearing is very likely to fail in a few days or even just hours, then that is very valuable. Today, our maintenance engineers already use augmented reality to go to the plants and see on the digital twin where potential bottlenecks are looming. I’m a big fan of this technology. Our order books are bursting at the seams. We are permanently producing at the capacity limit. A lost vehicle is a lost vehicle. I can’t make up for that with an extra shift from Friday to Saturday. Overall equipment efficiency is therefore extremely important for us. Ideally, a plant would run at 100 percent in 24 hours. That will probably never happen. But it makes a huge difference whether a body shop is running at 85 or 95 percent availability. That’s just one example. There are many more.

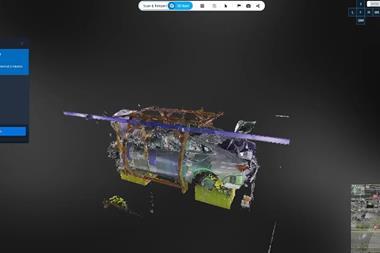

Our cars have long been semi-autonomous. Why do I still need armies of employees to drive the vehicles to the parking lot? The cars have to do that themselves. But to do that, we need systems that react very quickly. And that’s where 5G comes in. We are working hard to equip our plant site with 5G network so that such applications can become a reality. Another great example is our “Fata Morgana” application. During the coronavirus pandemic, we were unable to accompany start-ups abroad on site. So we developed a 3D world that basically allows us to be on the ground. We can even do remote repairs on control panels, for example.

Are these examples also a boost for Škoda’s entire production network? To what extent is the plant in Mladá Boleslav a blueprint for other factories?

Here in Mladá Boleslav we have an ethos of responding first in important issues at Śkoda. There is definitely competition among the plants, and that’s a good thing. But in the past, we’ve also seen time and again that innovations from other locations have migrated here to our headquarters. At the Indian plant in Pune, for example, a new application technology for underbody protection was developed that is significantly more cost-effective and at the same time less wasteful of material than previous solutions. This has made our painters here a little uneasy, but it is precisely this exchange of ideas that we thrive on, and I encourage it. Then there is the exchange between the group brands, especially in the volume group. I’ve known Christian Vollmer (VW brand head of production) for many years. We’re on the same page on this and have maintained great openness and transparency right from the start.

Škoda’s responsibility for the Indian market has already been mentioned several times. What product and production challenges does India pose for a European automaker?

The conditions in India remind me a lot of China. I was Chief Technology Officer for Volkswagen there from 2005 to 2010. When I arrived, we were building 230,000 cars a year at the time. When I left, it was over a million. And I remember the Polo, which initially didn’t run at all, with 40 percent localization. We managed to increase localization to 85 percent. That wasn’t easy. It was a time when by no means all the important suppliers were local. In India, I have a sense of déjà vu about this. Because we said right from the start that if we want to be successful with the four models we are building there, we need as high a proportion of localization as possible. We are currently at 92 percent - and that is still too low for me. We need a high level of localization for cost reasons alone. There is a brutal price war in the Indian market. If you want to produce a car there and import the parts or even the equipment from Europe, you’d be better off not trying. Many manufacturers have withdrawn from the market but we are sure that we will make it. We want to hold on to the trust that the group has placed in us.

How do you ensure that your employees in production go along with all these changes?

In July of this year, I was fortunate to celebrate 35 years with the VW Group. If there’s one thing I’ve learned in more than three decades, whether in Germany, China or here in the Czech Republic, it’s this: anyone with money can buy concrete, steel, iron, electrics and electronics, plant technology, foundries and press shops. In the end, people make the difference. We thrive on the knowledge and skills of our employees. We have been living this at Škoda for years. We run our own vocational schools, academies and our own university for the optimal training of our employees. In the area of further training, for example, we have a Lean Center, which some 20,000 employees have gone through in recent years. These fast-moving times in particular call for lifelong learning. There is not a day when I don’t learn something new.

To read the original Automobil Produktion article in German, click here

No comments yet