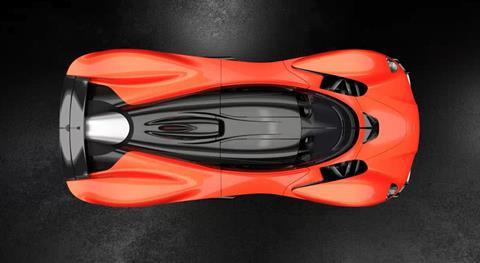

Cosworth has stepped up its operations to make the engine for Aston Martin’s Valkyrie hypercar

At the heart of Aston Martin’s new Valkyrie hypercar will be a hybrid power system built around a naturally aspirated 6.5-litre V12 engine generating 1,000bhp at a maximum 11,100rpm. This engine will weigh just 206kg in line with the vehicle’s overall aim to provide an optimal power-to-weight ratio, and forms part of the car’s structure as a fully-stressed element of the chassis.

The responsibility for designing and manufacturing the 150 units that can fulfil this exacting specification fell to Cosworth, specialist supplier of power system elements for high-performance cars both on the racing track and the road, which employs around 250 people in Northampton, UK. As Bruce Wood, Cosworth’s managing director for powertrain, explains, the contract to design and make the engines for the Valkyrie represents a mix of continuity and innovation in both technical and business terms for the company.

On the first of those counts Wood points out that Cosworth has had in-house manufacturing operations throughout its existence, but until recently they were largely confined to various components at prototype volume levels. “We could make things such as blocks, cams, heads, cranks and pistons but only for around 150-200 engines a year,” he confirms. These were produced small in volumes, but covering a wide variety of units, with perhaps as many as 10 different engines being built.

But there was also some production of complete engines for both track and road use. In 2008, for instance, Cosworth was appointed as sole supplier of engines to the Indycar series. A more prescient contract arrived in 2011, with Cosworth tasked to make 77 engines for the Aston Martin 177, which was, Wood notes, the carmaker’s “first million-pound-plus supercar”. As such, Wood says, the Valkyrie project is “in a sense a continuation of that philosophy” one that “perhaps makes Cosworth an obvious choice for providing the engines for hypercars and supercars coming out of racing.”

Boosting production operations

However, if Cosworth is to become a regular supplier of complete engines, even for the relatively small volume that might be required for ‘supercars’, then much more production capacity will be required than the handful of standalone machine tools that constituted its machining capabilities a decade ago. As Wood confirms, the necessary resource is already place in the form of the company’s Advanced Manufacturing Centre, a highly automated, flexible manufacturing installation, inaugurated four years ago at a cost of £22m ($27.6m).

The centre is, in effect, a 38,000 sq.ft factory in its own right, which includes eleven Matsuura four and five-axis machining centres with supporting capabilities including a gantry system for part loading and unloading and robotic tool change. Other features include a plasma spray coating system for cylinder bores and three coordinate measuring machines. The whole installation has ISO9001 quality accreditation.

The significance of the centre in business terms is, as Wood explains, that it turns Cosworth from a design and prototyping operation with some ancillary, minuscule production capacity, to one in which those first attributes are supplemented by genuine state-of-the-art machining capabilities able to satisfy the volume requirements associated with ‘supercar’ manufacture. Now, he says, Cosworth “can make about 20,000 parts, such as a cylinder head, block or sumps, a year”, a capability that he reckons makes for a potential total output of “maybe 5,000 complete engines.”

Until recently, though, the installation has effectively meant that Cosworth has acted as a tier one supplier of engine parts to OEM customers. Such work, says Wood, generally sees Cosworth “receive raw castings” with subsequent operations usually being “just machining with some sub-assembly of cylinder heads in terms of [valve] seats and guides for instance.” It currently has parts manufacturing contracts with two OEMs, one of which is Honda.

Nevertheless, even at that level the installation has made a difference to what the company can achieve. That has been achieved in part by cutting cycle times, Wood continues, “particularly non-metal cutting time”. As he observes “taking an hour out of production time, when only a small number are being made, doesn’t account for much, but it makes a huge difference when output is 5,000 per year.”

But, as Wood further explains, much more has been involved than just the application of new manufacturing technology. Instead, the company has got to grips with a way of working that simply was not part of its previous day-to-day experience and that has, he says, “been a revelation to us”. Essentially that involved “getting hold of a production mindset” with a focus on “driving time out of the cycle”.

The company did so in several ways, one of which was by tapping into appropriate sources of external expertise. “We got help from customers and our machine tool supplier,” states Wood. Another was by some judicious hiring. “We did recruit some key people,” he says. The manager of the centre, John Miller, for instance, joined from Toyota. But most of all the company simply learned by experience with a learning curve that, as he admits, flatlined for a while before starting to ascend at an increasingly steep angle. “We have got better at it,” he says. “OEE (overall equipment effectiveness) is now at around 70% but was probably less than half that at the start of our first year of operation. We clawed to make much improvement at first, then in the second year things were a bit better, but this year they have really taken off.”

The plasma coating technique was a process that took a while for the company to master, notes Wood, though it was not new to the company. “We have been using plasma spray bores for 20 years for motor racing,” he states, but it was only at the inception of the centre that Cosworth took delivery of its own in-house system from supplier Oerlikon. “Previously we would have sent engine blocks to Switzerland for treatment,” he explains, adding that like metal forming techniques such as casting and forging, the plasma process “has a bit of black art in it and is not 100% science as is the case for machining operations like milling and turning.”

The need for flexibility

Wood confirms that an absolutely key objective right from the first day of the centre’s operations was flexibility. Obviously the initial priority was that the installation be able to service the existing OEM parts contracts but, he emphasises, “we wanted to be ready for what might come next.” That is why, for instance, he describes the robot loading system as “very important”. As he explains “it is not impossible to envisage that in, say, five or six years we might have six or seven different contracts underway.”

Cosworth has so far generally not carried out final assembly of engines, but has instead shipped parts out to its customers, but this will definitively change with the Valkyrie engine. “We will build them in their entirety,” Wood confirms. “So, you could pretty much say this is our first complete engine production project.”

The engines will be manually assembled, starting in the last quarter of this year, in an existing space though with some use of automated support tools. There will, for instance, be automated recording of torques using Bluetooth-connected torque wrenches. “Every nut and every bolt will have their torque recorded so there will be a complete passport that goes with each engine,” Wood confirms. There will also be some use of barcode scanning, though Wood indicates that making 150 engines at rate of two a week will mean that a more human-centric approach can be employed. “We will have ‘one-man, one-engine’ assembly with a buddy checking system,” he states. He adds that cylinder heads will be assembled separately but on-site, as will pumps, so final assembly will effectively be “assembly of sub-assemblies”. He also confirms that an extra eight staff were hired for assembly work.

“We wanted to be ready for what might come next”

Bruce Wood, Cosworth

Building the supply chain

The project will also place Cosworth at the centre of an extensive supplier network. “We recognised that we would have to expand supplier quality considerably from very first prototype work two years ago,” says Wood. “We deliberately sought to select companies which could then become production suppliers, and about 90% of suppliers used for first prototypes have since gone on to be production suppliers.” There are around a hundred suppliers in total, most of them, Wood indicates, in the UK but with “a reasonable number in the US and a handful in Europe”.

One task that was considered for outsourcing, but which will be kept in-house, will be making wiring harnesses and looms for the engines. “Making the looms is a long process and we did look at outsourcing the task,” Wood confirms. “But we have always previously made looms in-house and so decided to continue that way.”

Wood says that current parts manufacturing contracts for the centre run for a little bit over another two years, while the projected production rate for the Valkyrie engines should also stretch that work over into the year after next. But he looks forward to what might follow without any trepidation and is confident that Cosworth is now set up for a future in which it can act as both a parts supplier and a provider of complete engines for the highest performing vehicles that any ‘supercar’ OEM can envisage.

No comments yet