With Fiat Chrysler and Renault failing to reach a deal to join forces, what are the prospects for the PSA-FCA merger?

In parallel to the proposed merger with FCA, Renault’s longstanding alliance with Nissan came under increasing strain, with the issues surrounding Carlos Ghosn probably tipping that arrangement over the proverbial corporate cliff edge. However, FCA still wanted a merger to protect itself going forward from the headwinds of electrification and global economic uncertainty; step forward PSA, run by ex-Renault executive, Carlos Tavares. With the acquisition of Opel/Vauxhall now proceeding well, costs being cut, platforms being shared (essentially Opel models being made on PSA platforms and GM’s history being erased), and new model programmes under way across the enlarged European PSA-Opel operation, Tavares needed another challenge; and with the now agreed merger with FCA on the table, he has his wish and a global one at that.

In its press release in December 2019 confirming the deal, PSA and FCA said that the combined company will be the 4th largest vehicle company in the world when measured by volume (c8.7m) and 3rd largest when measured by revenue (€170m). The new company will be especially strong in Europe (although it will also have a disproportionate presence in the low/no-margin small car sector), Latin America (complete with its economic problems) and in North America, largely through Jeep and Ram. But it lacks a major presence, nor an obvious strategy anywhere in Asia, with only PSA’s underperforming JVs in China of any note.

The December 2019 merger confirmation is, as is the case with such mega mergers, merely a staging post. The full merger will not be complete until early 2021, and plenty could change in the global and regional economies before then. FCA CEO, Mike Manley (a Brit, not an American interestingly enough) who will sit somewhere below Carlos Tavares in the new company’s hierarchy, told the press in January that he did not expect any major obstacles and that talks were progressing well. However, there are many challenges for PSA and FCA executives to address before the $50bn merger is complete.

Key issues to address

How will a further decline in Chrysler car and Ram truck sales globally impact FCA’s value? And how will January 2020s revelations that the Jeep Grand Cherokee has failed EU emissions tests impact the situation? The cash-cow that was Jeep may well have problems under the surface, and with an expensive new model programme only midway to completion, it needs the recently launched small Gladiator and pick-up, as well as forthcoming large models, Grand Wagoneer and Commander, to be successes and indeed gain some traction beyond the US.

Jeep and Ram especially have underscored any FCA profits in recent years, with the much-reduced Chrysler and Dodge ranges of marginal relevance – and if margins continue to fall in North America before Carlos Tavares can work his magic, what other American issues will have to be addressed when the merger is complete?

In Europe, Maserati continues to lose money (it was negative to the tune of around €150m in the first nine months of 2019), while Alfa Romeo continues to fail to meet sales objectives and financial targets. The late Sergio Marchionne had set Alfa the objective of achieving 400,000 sales by 2018 – but the brand achieved less than half that last year; and it has no obvious solution to these low volumes in terms of the model pipeline generating increased volumes.

More EV tech for FCA

More significantly, FCA is a real laggard in electric vehicle technology and, ahead of the PSA merger plan, FCA had agreed a deal with Tesla to “use” its EV emissions credits to counter its own problems in this area. In a bid to avoid even higher EU fines for excessive emissions, financial analysts believe FCA will have paid over €600m to Tesla, a welcome cash boost to Elon Musk no doubt, but hardly a long-term viable plan. PSA, it is true, has electric vehicle technology suited to small and mid-size cars and has already begun to use this on Peugeot, Citroen, DS and Opel models. No doubt such technology could be adapted to Fiat’s small cars, as well as Alfa’s slightly larger range (larger as in size that is, not volumes). Whether PSA’s electric platform can be translated on to the larger Jeeps and Rams especially, or if a new larger electric platform is required, remains to be seen.

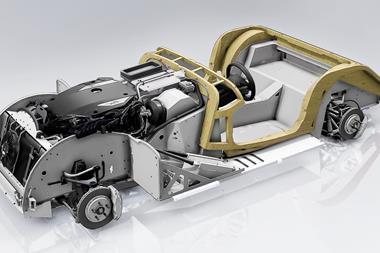

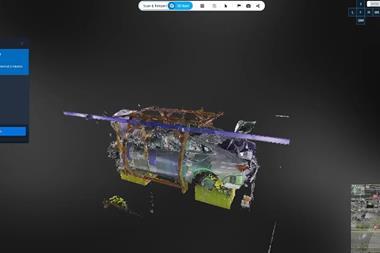

Messages coming out of Italy in December suggested that most of the combined PSA-FCA model range would be made on two platforms, namely the CMP and EMP2 platforms which PSA will – and now Opel – use for all future programmes. These will be eminently suited to Fiat cars and vans and Alfa cars. The expectation appears to be that up to 70% of the combined group’s output will be made on these platforms, with the larger Jeeps and Ram trucks, plus the larger Alfa and Maserati models using existing FCA architectures; the problem here is that while there are some monocoques Jeeps, e.g. Cherokee and Grand Cherokee, there are also a number of body-on-frame vehicles (Jeep Wrangler and Gladiator for example, plus the Ram pick-up range), many of which have their dedicated platforms or highly specific variants of a base platform. Achieving major cost savings and engineering synergies here will be a time-consuming and high investment challenge to put it mildly.

Several commentators have suggested that Carlos Tavares will look to apply some of his most successful tools from his turnaround at PSA and more recently at Opel when he finally gets his hands on FCA. In addition to accelerating platform sharing (for example replicating the decision to make the new Opel Corsa on the CMP platform was made soon after the Opel acquisition was completed and despite the loss of investment on a new Corsa platform under the GM ownership which PSA could have used), Tavares will look for manufacturing efficiencies; for example, working four longer days rather than five normal length days for example to save lighting and other operating costs in some factories. Other cost saving initiatives could include incentivising surplus labour to take redundancy terms as soon as possible (although the Italian and American unions will resist such entreaties quite forcibly), streamlining the dealership network and increasing competition between factories to win new work. We can expect Fiats to be made in PSA and Opel factories and vice versa before too long. This may help in Europe, and possibly Brazil, but elsewhere may be not.

All that is fine, and Tavares and his colleagues may well find a way to cut waste and duplication in Europe. It may even help expand in some markets, with the Fiat-Tofas Turkish plant ideally suited to making vans and entry level cars for the PSA/Opel brands for Turkey and its regional markets for example. But with sales of 8.7m and capacity (according to LMC) of up to 14m, something will have to be done in that regard. The American unions will resist plant closures, as will those in France and Italy, with these countries’ governments also highly wary of consequent deindustrialisation and associated job losses if factories close. The French government is well aware of PSA having moved 208 and C3 production to Slovakia and Morocco, and the 2008 to Spain; it won’t want any more PSA production to leave France, and how will the Italian government react to any further cutbacks on the manufacturing output across the Fiat factory network in Italy? Will domestic political pressures mean that Fiat Poland loses out in order to save Italian jobs? That is just one of the main unanswered questions which the new company – with its complex shareholder mix and political shadow puppet masters – will have to address.

Challenges in the Asian markets

But all of these issues which need addressing in Europe – and North America where excess capacity is likely to rear its head before too long if Jeep and Ram sales fall – fail to address the challenges in the rest of the world. While PSA has a modest presence in Latin America and Fiat is, along with VW, market leader in Brazil, neither company has any notable presence in Asia. How PSA-FCA, whatever it is called when the merger is complete, can call itself a global player without an Asian strategy is open to doubt. A few thousand models are imported into Japan, and very low production in India does exist; but these activities are minuscule by comparison to these markets’ overall size and potential. It is true that PSA has some operations in China, through joint ventures with Dongfeng produced only a little over 112,000 vehicles in 2019, against nominal capacity there of more than half a million units. If anything encapsulates the scale of the challenge of facing PSA before and indeed after it completes the merger that is it. If Carlos Tavares can solve not just the challenges facing PSA but also the combined company in the years ahead, he will really have earned whatever bonus is written into his contract!

No comments yet