James Bakewell reports on BMW’s growing use of additively produced parts in both vehicle personalising and series production applications

In 2006, when Dominik Rietzel was finishing his diploma thesis at university, his professor asked him if he would like to like to undertake a PhD in injection moulding. Rietzel was flattered, but replied that he thought the future of mass-production lay in a technology then known as rapid prototyping – additive manufacturing (AM). His professor, after thinking for a moment, suggested that if that was the direction he wanted to take, he should “pay a visit to a doctor”.

Rietzel went on to do his PhD in AM, during which he worked on a project with BMW. Then in 2013 he joined the carmaker, he says, “to work towards bringing AM to series production”. In 2018, as head of non-metals at BMW’s Additive Manufacturing Centre (AMC), he achieved that aim with the Mini Yours Customised programme.

Through the Mini Yours Customised website, a customer can personalise two AM products – a side scuttle and a decoration plate for the dashboard on the passenger side of the vehicle. The programme takes advantage of the inherent flexibility of AM processes. Using an online configurator, the customer can select a colour, change the pattern, and add words and an icon to these parts, which are then printed and shipped to them directly within a few weeks of the order.

Vehicle customising applications for AM

Shortly after joining BMW, Rietzel says he and his team were looking for “killer applications” for AM within the BMW Group, and quickly hit on the idea of personalisation. The team’s logic was sound – the personalisation of vehicles was already a lucrative business. For instance, since the UK’s Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA) made personalised number plates available in 1989, more than 4.5m have been sold, raising about £2.3 billion in revenue. More recently, Nissan has reported a surge in demand for personalisation on its Micra. Approximately 22% of Micra buyers are choosing to tailor the exterior of their vehicles, spending an average of €400 ($455) each on so-called personalisation packs to do so.

However, the number of variables a customer can play with using such personalisation systems was actually quite limited. Rietzel believed that through the use of AM, BMW customers could be granted greater freedom of expression. He says: “The question we asked ourselves was, ‘what if you could use AM to create your own special editions?’”

Of all BMW’s products, the premise seemed to fit well with Mini. The brand has a cult following and is highly popular with young people, meaning there is more scope there for experimentation in comparison with BMW’s more conservative marques.

The first concepts were drawn-up in 2013 and in 2015 AM parts were field-tested for DriveNow, BMW’s carsharing service. Through this test, nameplates were produced for 100 Minis using Carbon’s CLIP technology. The response from this test was good and in April 2016 Rietzel was told he could try the technology in full-scale production. There was a catch, however; he had to do so by the start of production in January 2018: “I went back to the team and told them that we would have a lot of work to do over the next year-and-a-half.”

The first step was to define the products with a design team. Once this was settled, Rietzel says he had to “create fans” in all of the other departments – such as IT, aftersales, materials research and marketing – that would be involved in bringing the products to market.

AM processes to meet high standards

Then Rietzel and the team had to select AM processes capable of producing the parts to BMW’s exacting standards. The decorative plate for the dashboard, for instance, has to be produced to the tightest of tolerances. It has to be suitable for the customer to fit by hand – Rietzel was adamant that the installation of these parts shouldn’t require visits to the dealership. Further, it has to remain intact in the event of a crash so as not to put passengers in any further danger.

The parts are produced at the AMC using a variety of AM platforms including Carbon’s CLIP, HP’s Multi-Jet Fusion and EOS’s selective laser sintering (SLS) technology.

BMW is a long-standing partner of HP and EOS, and invested in Carbon in September 2016. Carbon claims its CLIP technology enables parts with high-quality surfaces to be produced more rapidly than is possible using conventional methods.

Using the process, light is projected through an oxygen-permeable window into a reservoir of ultraviolet (UV) radiation-curable resin. As a sequence of UV images are projected, the part solidifies and the build platform rises. The heart of the CLIP process is the dead zone, a thin liquid interface of uncured resin between the window and the printed sections of the part. Light passes through the dead zone, curing the resin above it to form a solid part. Resin flows beneath the curing part as the print progresses, maintaining the continuous liquid interface from which the process draws its name. Once a part is printed, it is baked in a forced-circulation oven where heat sets off a secondary chemical reaction that causes the materials to strengthen.

The resulting parts are hand-painted at BMW with a specially developed two-layer system that gives the premium surface finish required by the carmaker.

Once Rietzel and his team had final approval for the parts, they had to create a system that would enable them to be produced. They had to develop a configurator that guides the customer through the part design process, and also to ensure that in adding text the customer didn’t breach any copywrite or obscenity laws, developing an automated blacklist of words and terms that couldn’t be added to the parts. A manual review system is in place for more complicated cases.

Once the customer has designed the part, the order moves to an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system and, in parallel, to a manufacturing execution system built on an in-house platform BMW developed in 2011 for producing prototypes. Rietzel says: “This was a tough challenge, as there was no service provider who could do this for us. Files go into the system and are automatically placed with a machine where they are produced, then move onto the paintshop, before being packed and sent to the customer.”

There are many quality control steps in between. Each part has a unique identification code that is readable using a camera monitoring system and provides a host of production information, which enables any problems to be rapidly identified and ironed out.

Given that Rietzel is unable to discuss production figures, the success of Mini Yours Customised is difficult to gauge. Certainly, customer feedback appears to be overwhelmingly positive and the experience and expertise gained through the programme will almost certainly be invaluable. Rietzel says: “BMW don’t do showcases. We want to prepare ourselves to use AM wherever it is needed and can help us.”

Further commercial applications of AM are highly likely, especially given that the BMW Group has taken the decision to invest more than €10m in a new Additive Manufacturing Campus. Located in Oberschleissheim, just north of Munich, the 6,000 sq.m facility will accommodate up to 80 employees and over 30 industrial systems for metals and plastics. It is scheduled to go on stream in early 2019. Rietzel concludes by saying that Mini Yours Customised was just a starting point: “we want to do many more things.”

One million AM-printed parts in series production

AM maybe relatively nascent technology, but BMW was an early adopter and in the last decade the company has used over 1m printed parts in series production. This year alone, the carmaker expects to produce 200,000 components using AM – an increase of 42% compared with 2017.

For series applications, it uses AM to produce components that would otherwise be unpractical using other processes, and before Mini Yours Customised, the technology was only been applied to high-end vehicles. For instance, plastic holders for hazard-warning lights, centre lock buttons, electronic parking brakes and sockets for the Rolls-Royce Phantom have been made using AM since the start of production in 2012.

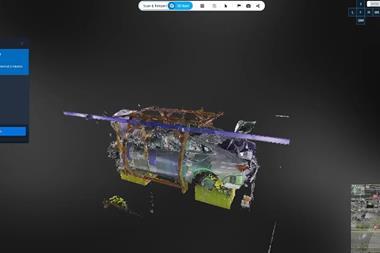

The i8 Roadster features two parts produced using AM processes. Indeed, the millionth part produced by BMW was a window guide rail – part of the door that allows the window to rise and fall smoothly – for the hybrid-electric sportscar. The rail took just five days to develop and was integrated into series production at the carmaker’s plant in Leipzig shortly after. The component is manufactured using HP Multi Jet Fusion Technology, which is capable of producing up to 100 window guide rails in 24 hours.

The first AM part to feature on the i8 Roadster was the fixture for the soft-top attachment. Made of aluminium alloy, the metal component weighs 44% less than the injection-moulded plastic part that is normally used, but is ten-times stiffer.

The BMW Group expects that, with time, it will become possible to produce components directly where they are ultimately needed. The head of its Additive Manufacturing Centre, Jens Ertel, says: “We are already using AM to make prototype components on location in Spartanburg, Shenyang and Rayong. Going forward, we could well imagine integrating it more fully into local production structures to allow small production runs, country-specific editions and customisable components – provided it represents a profitable solution.”

No comments yet