There may be less reliance on automation at Scania’s Johannesburg plant but flexibility and workflow keep operations in smart shape for the needs of its commercial vehicle customers

South Africa’s commercial vehicle segment is full of fierce competition. It is the largest contributor to the commercial vehicle market in Africa, with over 50% share. It is also a growing segment.

According to figures from the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa (Naamsa), sales of medium- and heavy-duty commercial vehicles rose by 19% and 18.8% respectively in 2019 compared to 2018 figures. The organisation has also predicted a further rise in sales in 2020, citing increasingly positive economic conditions and growing customer confidence as stimuli for new vehicle trading.

The number of vehicles assembled locally gradually started declining in the 1980s due to the limited availability of raw materials and an influx of low-cost vehicles imported from other countries. But with government support for local production, some companies are eyeing a bright future for their plants.

The long-haul market is particularly competitive. Scania and Volvo Trucks are among the top producers in this segment, and both operate complete knocked-down (CKD) facilities in different parts of the country.

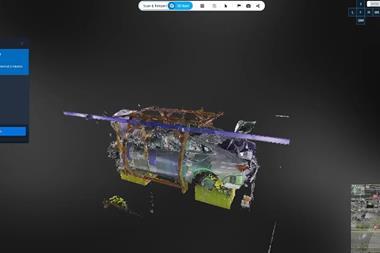

Trucks and buses roll out of Scania’s assembly facility in Johannesburg. Most of these are then sold locally, while some are exported to other neighbouring African countries. The plant, which opened in 2003, employs around 75 people and is a CKD operation, with chassis assembled on the lines and other parts such as the cab shipped in from Brazil.

Speaking to AMS, assembly plant manager Deon Flusk explains the way in which the plant is similar to others in the Scania production network. “Our facility is wholly owned by Scania and the VW Group,” he says. “So what you see out here is pretty much the same as what our colleagues will do in the larger plants that are located in Sweden and elsewhere, but we just do it on a smaller scale. This means that many of our processes are manual. We don’t have high end electronic tooling that our colleagues do, though we produce the same trucks.”

Pneumatic drills are constantly being used by workers on all parts of the line as they fix various components to the chassis. The care and attention to detail is clear, with each person checking and re-checking their work after every step.

One part of the process that is particularly important, Flusk continues, is the fitting of the pipe bundle: “It is attached to various solenoid valves and air tanks. It’s the veins of the vehicle along with the electric harness. If the pipes are in the wrong position, then it will cause a major deviation.” As a result, checking on this station is meticulous.

With manual processes at the heart of the Scania plant, not much has changed over recent years in terms of technology. However, the plant itself has undergone a transformation.

The production line at the plant has not always been able to make both trucks and buses. There were previously two lines, one dedicated to trucks and the other to buses, but this changed in 2015. “We consolidated our truck and bus into one production line because the bus volumes dwindled,” Flusk recalls. “We challenged the status quo and decided to try and produce both on the same line. It was difficult for us, but we managed it with a bit of tweaking.”

The way in which Scania operates in the country is quite complex, Anders Friberg, commercial director of Scania Southern Africa, tells AMS. “We have divided South Africa into four different regions: the south western Cape Town area, the eastern area around Durban, the central area around Bloemfontein, and the biggest region which is Gauteng with Johannesburg. Each of these has a regional director, a sales manager, aftersales manager and a workshop manager.”

As well as overseeing Scania’s activities in the local market, Friberg is also responsible for exporting vehicles from South Africa to other countries. These include Namibia, Botswana and Mozambique. “There we have more or less the same set up with general managers and sales managers,” he notes.

Scania also exports vehicles from South Africa to Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi, but instead of using its regular set up, the company is working with independent dealers. This is due to the low volumes that are currently being sold in these countries. Asked if there is scope for setting up manufacturing facilities in other African countries, Friberg does not rule it out. However, the current focus, he adds, is on increasing sales rather than expanding the production footprint.

The main factor governing the sale of commercial vehicles in South Africa, Flusk suggests, is the sheer size of the country. “It is still a market predominately centred on long-haul trucks,” he comments. “If you look at the map and the distances, people move goods a very long way here. The average hauler today is doing roughly 15,000km a month, or about 180,000km a year.”

Scania is one of the top sellers in the long-haul segment. Along with Volvo and Mercedes, the three companies hold about a 65% market share. Flusk believes that the quality of Scania products and their reliability has secured its position here.

Instead of trying to gain more market share in the long-haul segment, the company is currently focused on segments that it does not perform so well in. “We have only a 5% market share in the construction segment, but Mercedes have 45%,” Friberg states. “So our focus is to grow here. We also need to look into the distribution segment too.”

The markets for tipper and mixer trucks in South Africa could be of particular interest for Scania. Flusk believes that the company could start producing models for this segment locally if demand is strong. However, he is quick to point out the fact that customers can be tricky to please.

“Customers in these segments won’t wait,” he warns. “In fact, they want the truck yesterday, so we need to have it ready for them before they even ask. And sometimes the truck won’t be 100% with all the trimmings exactly how they want it, but if we can fulfil 95% of all the customer’s needs then they will be happy.”

To do this, there needs to be stock ready for sale to any prospective customers, and it must be easily adaptable. As well as expecting a truck immediately, companies often want them to be customised to suit specific needs. Scania uses what it calls a “late formation of variant codes” system, or LFV for short.

“So for example, we have a G460 in stock now in our yard, but a customer comes in and wants a G410,” Flusk muses. “Instead of ordering a new vehicle we use LFV to downgrade the G460 so the customer will have a G410. This allows us to reduce the customer’s lead time and reduce our stock here, as we don’t want to keep too much stock because it’s just tied-up capital. So there is a lot of flexibility in our system to get the right vehicles for our customers. It’s all about planning and our workflow as well as being close to the customer and understanding their needs.”

One of the major challenges with this approach is logistics. Spare parts must be readily available to enable customisation, so the facility is “extremely tight on the schedule delivery of parts.”

As for being close to the customer, Scania is consistently carrying out research and speaking to clients in the hope of identifying their needs. This is the same in South Africa as it is across the other countries in which the company operates.

“We need to listen to the industry,” Flusk emphasises. “It might mean we have about six or seven different models going down the line. At the moment, around 70% of the vehicles running down the line are in the long-haul segment, but we can definitely see the construction segment is coming up for us. Our competitive edge comes with our modular production system, and the ability to be flexible in changing parts and components between the different variants.”

Looking further ahead, the subject of Industry 4.0 and the idea of introducing automated systems to the plant is of interest to Flusk. He is cautious, though suggests that certain processes could benefit.

“Investment depends on what our output is,” he states. “We need to think about it outside the box. Even though a lot of our processes are manual, we need to have the same quality as other plants in the Scania network that might have higher levels of automation. And we are doing really well at the moment.”

AMS on Africa

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Currently reading

Currently readingAMS on Africa: Part 5 – Heavy-duty headway at Scania

- 6

No comments yet