Systematic investment since 2010 has modernised the facilities, production processes and workforce skills at GAZ's key factory. The new discipline has improved efficiency and quality at this complex operation

Even before you reach the production areas of the GAZ plant in Nizhny Novgorod, the site’s character is made apparent by two sets of graphics displayed on the walls of the corridor that leads from the reception. One features images of trucks produced as far back as the 1930s, illustrating its role in the foundation of the Russian automotive industry; since inauguration, the plant has produced 18m vehicles of all sorts. The other comprises a series of charts relating to just the last 24 hours, in which a pointer indicates the current quality levels of specific vehicles out on the shopfloor; this emphasises a determination to further Nizhny Novgorod's reputation as a practitioner of the most modern production techniques.

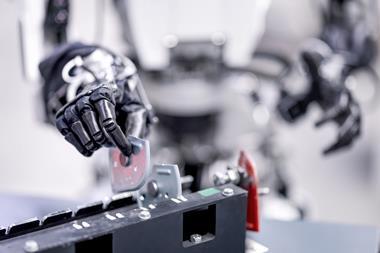

That plural is entirely apposite because manufacturing at the plant is very unusual in its multiplicity. At the largest scale, it involves a mix of GAZ’s own commercial vehicle manufacturing and contract production of both vans and passenger cars for other OEMs with high levels of automation. In addition, there are several smaller-scale sub-system assembly operations in which GAZ acts effectively as a tier-one supplier – in some cases autonomously, in others as a joint-venture partner. Altogether, these activities require a workforce of 24,000 personnel.

There are four separate conveyor lines on the main shopfloor and the production technologies in use are consistently modern, implemented by personnel trained in appropriate quality-related techniques. Arguably the most distinctive feature of the facility is how all these processes are not merely physically co-located but integrated into an overall environment that is consistent in its ethos and attitudes.

Day-to-day problem-solving meetings, for instance, take place in a room to the side of the main production floor, known as 'the war room'. They are always concise and seldom allowed to go beyond 30 minutes, confirms GAZ group president Vadim Sorokin. The location, he adds, means that, “We can see the conveyor from here. We can go out to look at situations on the line in close-up if need be.”

Supply chain challenges

Sorokin explains that GAZ takes a similarly brisk and proactive approach to solving any problems that may occur in its supply chain. If, for instance, the tier-one supplier of a sub-assembly is let down by a component supplier further along the chain, then GAZ is prepared to use its own weight to help resolve the issue. It will even send a car directly to the tier-two operation to collect the missing parts. As a last resort, the OEM also has the flexibility to reschedule its own operations at just a few hours’ notice.

The ‘war room’ is for more than just addressing ‘goods inward’ issues. There is also a substantial and important ‘information inward’ aspect, with important implications for logistical and also production processes. This, explains Sorokin, takes the form of continual feedback from dealers about the performance of components on vehicles that are still in warranty. Dealers, he reveals, send information every day on all relevant repairs they have carried out in the previous 24 hours and that information is “intensively monitored” to identify the cause. Appropriate action is then initiated to remedy the situation at its point of origin, whether that is in-house at GAZ or at the supplier. “We will continuously update information on faults per supplier, how many there have been, at what mileage, who is responsible, the status of remedial actions and due dates for its completion,” says Sorokin.

"We will continuously update information on faults per supplier, how many there have been, at what mileage, who is responsible, the status of remedial actions and due dates for its completion" – Vadim Sorokin, GAZ

Interestingly, Sorokin adds that this continual focus on improving product and process quality through defect detection and analysis is not just quantitative in its approach – in other words, it is not simply aimed at identifying the most frequent problems. It also takes into account the fact that, as a manufacturer of commercial vehicles, GAZ’s own customers are in business and therefore faults in its products can affect their performance. So, Sorokin states, “We analyse this database to see what defects may have caused customers to lose business.” Apart from the potential effects on customers, these faults are also most damaging to GAZ’s own reputation and so receive special attention. But such faults are "very rare”, adds Sorokin.

Continuous development

All this improvement has taken place over the last few years against a background of constant upgrades to support an intensive programme of new product introductions. “There has been a major modernisation every year since 2012,” confirms Andrei Sofonov, head of production for the LCV Division. He is also keen to point out that GAZ manages to run this complex set of operations at a high level of efficiency. “There have been no unplanned shutdowns this year,” he notes.

On the main production floor, the aforementioned initiatives have related to both new GAZ vehicles and to the start of various contract manufacturing operations for other OEMs, the number of which has increased over the last half-decade. Production of the Skoda Yeti started in 2012, with the Octavia and VW Jetta beginning the following year. The total investment made by all parties was €300m ($332.2m).

Hardware installations on the shopfloor have been upgraded and the skills of the workforce have been developed, with part of the OEMs’ cash spent on fitting out a 3,000 sq.m training centre to develop five specific areas of expertise: welding, painting, assembly, production systems and logistics. Training is carried out by GAZ staff who have previously been trained at Volkswagen and Skoda plants in Germany and the Czech Republic.

In 2013, another contract manufacturing initiative began which, superficially at least, seems more in tune with GAZ’s own identity as a producer of commercial vehicles. This was the agreement with Daimler to produce Mercedes-Benz Sprinter vans. The assembly line is an impressive installation that saw the upgrading of 90,000 sq.m of floorspace to house both assembly and associated logistics facilities. The 10,000th Sprinter was made at Nizhny Novgorod in May this year. Engines for the vehicles are also made by GAZ, at its powertrain plant in Yaroslavl.

Paintshop innovation

The Sprinter benefits from another recently constructed facility at Nizhny Novgorod – a new paintshop, the contract for which was signed between GAZ and painting systems supplier Eisenmann in May 2012. This involved stripping back a former press shop to nothing but the barest structural essentials – the pillars, beams and outer shell.

One innovation introduced by GAZ is a 30-degree body swinging system that has been integrated into the process of e-coating. This ensures that all the internal cavities of the body are filled with primer. Trial runs validated the concept after a couple of vehicle bodies were put through the process and then cut up to check in detail that all areas had been satisfactorily covered. Sorokin says that, because the vehicles painted in the facility include Sprinters, Mercedes-Benz had to be given approval as well. He adds that the severity of a Russian winter was not allowed to interfere with the build schedule; temporary covers were placed over window cavities and powerful portable heaters allowed work to continue even when the external temperature was well below zero.

GAZ’s own input to the development of the new facility has involved maximising the use of the skids on which vehicle elements are mounted. Sorokin explains that a way was found to mount two cab shells simultaneously on a single skid – something that Eisenmann did not initially believe possible. Otherwise, the skids carry one main body shell, and the painting process itself involves automated procedures for the cab and body interiors and exteriors, while doors and engine compartments are treated manually.

The new paintshop at GAZ Nizhny Novgorod, equipped by Eisenmann, handles both GAZ and Mercedes-Benz vehicles

The new paintshop at GAZ Nizhny Novgorod, equipped by Eisenmann, handles both GAZ and Mercedes-Benz vehiclesWaste material from the painting process is piped to a treatment facility that can cope with both acidic and alkaline materials. According to Sorokin, the water undergoes three levels of processing – in the paintshop’s own treatment unit, in the corresponding plant-wide installation, and finally in the city’s own facilities – before it is released back into the environment.

Russian Machines’ CEO, Manfred Eibeck, oversees a set of operations that encompass rail engineering and aerospace maintenance, but GAZ remains a vital part of the conglomerate, providing 80% of its revenues. Even by itself, Eibeck concedes, GAZ is effectively “a lot of different companies”.

Eibeck observes that several years were needed after the initial acquisition of GAZ in order to make the company ready for serious investment. In particular, manufacturing processes were refined with the introduction of an approach based on the Toyota Production System, an initiative paralleled by the implementation of an effective quality management system.

Since then, however, investment in both products and production facilities has been heavy and continuous. Eibeck reports that during 2010-14 it amounted to 34.5 billion roubles (more than $1 billion). Over the same period, revenue per employee jumped by 61% from 140,000 roubles per month to 226,000. The general upskilling of the workforce was also reflected in a near quadrupling of the number of high-performance workplaces, from 5,600 to 20,800.

Appropriately, a major new addition to the company’s flagship GAZelle range of light commercial vehicles was launched in 2013. This is the GAZelle NEXT family that started with a drop-side truck and has continued since with variants including a cargo-passenger vehicle with crew cabin, and a microbus.

GAZ Nizhny Novgorod produces its own commercial vehicles but also undertakes a considerable amount of contract manufacturing

GAZ Nizhny Novgorod produces its own commercial vehicles but also undertakes a considerable amount of contract manufacturingEibeck foresees this approach continuing, with GAZ remaining a combination of OEM, contract manufacturer and tier-one supplier. Arguably, its ability to fulfil all these roles is the logical consequence of its original guise in the former USSR as a monolithic, completely vertically integrated operation – a structure now infused by a relentless drive for continuous improvement and a willingness to learn from best-practice worldwide.