Vehicle makers and tier suppliers are embarking on huge changes to their production operations and range line-ups to supply electrified vehicles. Ian Henry looks at who’s charging ahead and who’s falling flat

Just about every major car company has entered this rapidly changing market with gusto, although FiatChrysler is currently lagging behind. Meanwhile Chinese, Korean and Japanese companies have come to dominate the battery market and even where vehicle companies, including Tesla, have opened their own battery factories, they are dependent on one of the global battery players for core technology; in Tesla’s case it is Panasonic.

The shift to electric vehicles also has a very important political dimension, whether on a local scale in the sense of regulatory policy (such as limiting the use of petrol or diesel cars in urban areas), or on an international scale, e.g. China taking control of much of the world’s lithium mining industry. In this regard, the US government has taken note and shown an interest in fighting back, possibly belatedly; it is understood to be in discussions over taking a stake in London-based mining company TechMet to gain privileged access to new sources of lithium. In the same light, highlighting the politicisation of the industry, Volkswagen is understood to be in discussions with the Serbian government over preferential access to that country’s recently identified lithium deposits; and in return for this investment Volkswagen is expected build a factory in the country capable of making 150,000 and possibly more cars per year, powered not by electricity using batteries made with Serbian lithium, but internal combustion engines made elsewhere in Europe.

With the above in mind, this review looks at some of the recent, significant developments in electric vehicle (EV) production, the expansion of battery production and the developing infrastructure which will be vital to the successful move away from petrol and diesel engines alike. Given the fast-moving nature of these topics, this review is only a snapshot in time and an introduction to this evolving sector, rather than a definitive survey of everything which is happening at present.

The ‘skateboard’ platform

Traditionally vehicles have been built using either body-on-frame or unibody constructions; EVs based on existing platforms can use either technique but proprietary EV platforms tend to involve a third way, using what is known as the “skateboard” model. This is used at Audi in Brussels for the new e-tron range. It involves the vehicle being built in two sections which are joined together in a system similar to the body-on-frame method. The e-tron’s lower section – or skateboard – is built around a 700kg enclosed battery pack, using a welded aluminium spaceframe. Once three electric motors have been attached to this power pack, the lower half of the vehicle is married to the upper half. This upper half is built in a conventional manner, proceeding through the body, paint and initial trim stages, before the lower and upper halves are brought together and joined automatically using with flow-drill screws. The skateboard system will also be used in a new joint venture programme announced at the end of April, between Ford and Rivian, a new EV company in US. Ford will use this system in new vehicles to be made through the 2020s.

EV production highlights

Keeping up with developments at established and new vehicle companies is a challenge. Some of the most significant and interesting developments globally are discussed below.

We start with Tesla, which has been nothing if not disruptive to the established order. Despite failing to meet its production targets for the Model 3 (its offering in the volume segment), it has continued to expand its range. Its newest model, scheduled for full production launch later this year, is the Model Y, a mid-sized SUV. This is intended to outsell the existing Model X, S and 3 combined, and is targeted at the forthcoming Audi Q4 e-tron and existing Jaguar I-PACE.

Meanwhile, Volkswagen is leading the way in Europe and is converting three of its German factories – Zwickau, Emden and Hanover – to make EVs. With EVs also to be made in the US and China, VW is aiming for 20m EV sales cumulatively by 2028, of which nearly 12m are due to be made in China. VW EVs will be sold under the ID brand, while Audi will mainly use the e-tron label attached to existing model names. Seat will also launch EVs, with six electric and plug-in models expected by 2021. These will be the electric version of Mii and the new el-Born (which will be made by Volkswagen in Zwickau), plus hybrid versions of the Leon and Tarraco, Cupra Leon and forthcoming Formentor. Porsche meanwhile has its Taycan EV sports car almost ready for launch and currently undergoing final testing in hot and cold climate locations. Meanwhile in China, VW showed the near-production-ready ID Roomzz, a large three-row electric crossover, in Shanghai recently; it will go on sale in China in 2021. VW is also considering buying a controlling stake in its Chinese EV partner, JAC, possible now that ownership rules have been relaxed. In total the company is investing €44bn in EVs, equivalent to 1/3 of total group expenditure between 2019 and 2023.

Daimler meanwhile has started production of the EQC in Bremen, with EVs also due to be made in other German plants, as well as in China and at Tuscaloosa in Alabama. It has put Smart into a 50:50 joint venture with Geely, and plans to transfer all Smart production to China, making Smart into a purely electric brand. Once this transfer is complete, the existing Smart factory at Hambach in eastern France will switch to making the Mercedes EQA (effectively the electric A-class).

Somewhat behind the curve in terms of EV development is PSA which has recently begun its launch of E-tense models, the sub-brand for its electric vehicle range. The first of these is the DS3 Crossback small crossover; the E-tense version will offer a 200-mile range, and is powered by a 50kWh lithium battery and features advanced energy recovery during deceleration and braking

EV developments are also taking place at some of the lower volume manufacturers. For example, Aston Martin showed the Rapide E at the recent Shanghai motor show. Just 155 of this model will be made at the new Aston factory at St Athan in Wales; it will use batteries co-developed with the Williams F1 team’s commercial arm. Production will begin in late 2019; further EVs will be made at St Athan from 2022, start with an electric Lagonda SUV.

Meanwhile in the US, Ford and GM are steadily growing their EV offerings. FCA by contrast is notable for its absence from the EV space. GM is expanding existing its EV facility in Orion Township where the Bolt is made. This factory is receiving investment of US$300m with output growing to at least 50,000 units a year; significant though this may seem, it is small beer compared to the volumes planned by Volkswagen and the Chinese companies. Ford is adding EV production at Flat Rock in Michigan and will make a variety of models on a new flexible battery architecture, part of the co-operation with Rivian mentioned above. In parallel it wants to extend its fledgling partnership with Volkswagen by gaining access to VW’s own modular electric MEB platform. Ford is also developing solid-state batteries, jointly with Solid Power, a US tech start-up which raised funds in 2018. These batteries are said to produce 50% higher energy output than lithium-ion units, as well as offering numerous design and weight-saving benefits. In parallel, Ford will launch 16 electrified vehicles in Europe, including plug-in versions of the Kuga and Tourneo Custom, as well as the Fiesta in full and mild hybrid formats. A full electric Transit van will arrive in 2021. And in China it plans to launch 10 full EVs over the next three years, with much of the specific engineering for this programme taking place in Nanjing.

The Chinese are, as indicated, at the forefront of EV developments. Names unfamiliar to many in Europe and North America are very much to the fore here. For example, BYD (Build Your Dreams) is only just inside the top 20 vehicle companies China, but is actually no.1 in new energy vehicles, with its EV and plug-in hybrid range. It sold nearly 47,000 new energy vehicles in March alone in China, well ahead of BMW and Mercedes. Meanwhile, Chery-owned Qoros, which failed to make a name for itself as new Chinese brand to take on the Europeans in conventionally-powered vehicles, is now reinventing itself as an electric brand. Jinkang Seres, another new electric brand (which actually owes its origins to Sokon, a Silicon Valley start-up), will build a new $600m automated plant in Chongqing to make SUV with 500km range.

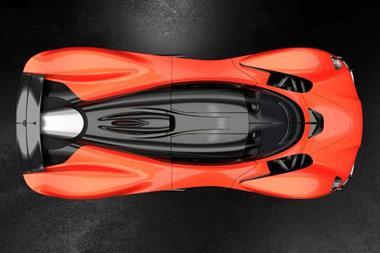

Geely is launching all new brand, Geometry. This will have 10 models by 2025, including sedans, SUVs, crossovers and MPVs. These will use CATL’s lithium batteries, with ranges up to 410kms. Geely also backing Lotus’ move into electric vehicles, with the Type 130 electric hypercar. Another interesting EV development in China is at Polestar, Volvo’s high performance brand; this will make EVs in China, at Luqiao in 2020, based on the existing CMA (40 series) platform.

Renault too is also looking at China for opportunities in EVs. At the recent Shanghai motor show it launched a small SUV EV: the K-ZE A-segment model will be made at Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi-Dongfeng joint venture plant, called eGt New Energy Automotive.

Battery developments

EV manufacturing involves much more than just developments at the vehicle companies. Central to this sector is the establishment of a viable battery manufacturing network. Most of the key suppliers are Asian, but the European vehicle manufacturers are encouraging the battery companies to invest heavily in Europe. For example, VW wants SK Innovation (SKI) of Korea to build more plants, each with minimum 1 gigawatt capacity; anything smaller would not make sense for VW which plans to buy €50bn of battery cells/packs over the next five years from SKI, LG Chem, Samsung and CATL. To enable this, SKI is currently building a battery cell plant in the US to supply VW Chattanooga in Tennessee from 2022. Ahead of this, LG, Samsung and SK are all expanding in Europe, as is CATL in China, all to supply VW with batteries from late 2019 onwards

SKI has also grown in Hungary; its first plant there will be operational during mid-2019, and a second plant will be operational within three years. The Korean company is making an initial investment of $777m, just to supply Mercedes. This news came out not long after CATL said it would build the biggest battery in the world in Erfurt to supply all the German VMs.

Another Korean company, LG Chem, has recently raised $1.6bn to finance a significant battery production capacity increase. This will be especially for VW-Audi and Renault-Nissan; it has new plants in Poland and China under way, with more to come.

Meanwhile, Mercedes has started building its own battery plant at Bruhl, near its Stuttgart headquarters. This is a key part of Mercedes’ own €1bn battery production network which will consist of nine factories at seven locations across Europe, the US and China.

The infrastructure challenge

It is far from clear whether governments across the world, except possibly in China, have fully got to grips with what is required in terms of supporting EV infrastructure. A couple of years ago, the UK was said to need as many as 10 Hinckley PoHinint power stations to meet projected demand from EVs at that time. Since then, expected EV growth rates have increased, so even more additional power generation capacity is likely to be required. However, given the UK’s recent poor track record with such infrastructure projects, it seems unlikely that sufficient power generation capacity will actually be built. The lack of progress in this area is attributable to potential Chinese power generating suppliers being deemed politically unacceptable or Japanese companies’ financial difficulties. And, as well as questions over whether the UK will have sufficient power generation capacity, there is much concern as to whether the existing power distribution networks are robust enough to enable the government’s aim of eliminating conventional powertrains in new vehicles by 2040, let alone the idea of his being achieved by 2030 as desired by some pressure groups.

Recognising the problem, the industry’s European trade body, ACEA, has recently suggested that consumers are holding back on buying electric cars in Europe. It attributes this to a number of factors, partly the price of EVs, but especially the lack of suitable charging infrastructure, a problem which exists across Europe. According to ACEA, there are currently only around 150,000 public charging points in the EU, but at least 3m will be needed by 2030, and that number is said to be based on conservative forecasts. ACEA has called for a major push by national governments and EU policy makers to accelerate the expansion of the EV charging infrastructure; whether its request, and its implicit warning, will be headed remains to be seen.

Given the lack of coordinated government action, both nationally and across Europe, it is possible that parts of the private sector will have to take the lead. For example, Stuttgart Airport is installing a charging network, using Mahle’s associate company chargeBIG; this will allow airport employees and fleet operators to charge their cars while parked at the airport. However, this is a modest development with just 110 charging points to be installed. Another modest, but potentially significant, move is taking place at Renault. The French company is piloting vehicle-to-grid infrastructure for EVs. It has fitted the latest technology in this area to 15 of its Zoe EVs initially. It will trial the system in a specific area of Utrecht in the Netherlands and on the island of Madeira. It has plans to trial the system also at unknown locations in France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and Denmark. By contrast, Skoda is installing 7,000 electric charging points at its factories for employees. It has already spent €3.4m on electric charging infrastructure at its headquarters at Mlada Boleslav. From small things, big things will one day come, but there really is a very long way to go.

No comments yet