Ford Otosan’s Inönü plant houses an unusual production mix, and is taking on more projects. Michael Nash investigates

Inönü is a small, sleepy town in north-west Turkey. The nearest city, Eskisehir, is a 40-minute drive away and is populated by young students who attend its two universities. Aside from an array of dilapidated houses and ancient-looking coffee shops, Inönü is home to a large Ford Otosan plant that opened back in 1982.

Inönü is a small, sleepy town in north-west Turkey. The nearest city, Eskisehir, is a 40-minute drive away and is populated by young students who attend its two universities. Aside from an array of dilapidated houses and ancient-looking coffee shops, Inönü is home to a large Ford Otosan plant that opened back in 1982.

But this isn’t any old factory in the middle of nowhere. It houses an unusual production portfolio, churning out trucks and tractors as well as 9.0-litre and 12.7-litre, six-cylinder engines for heavy commercial vehicles (HCVs), and 2.2-litre, four-cylinder Duratorq engines for Transit light commercial vehicles (LCV). It is also Ford of Europe’s only production centre for rear axles of the Transit models, and will soon feature in-house transmission manufacturing.

Speaking to AMS, plant manager Aysan Hosver outlines the advantages of making these components and vehicles under one roof. “Although they are used on different types of vehicles, the components of the engines have similar manufacturing processes,” he explains. “Having both in the same plant increases efficiency, and we can leverage the combined know-how and experience. We also benefit from flexible, low volume HCV production and a more automated, higher volume for LCVs. Machines and lines are designed in such a way that they backup each other in case of any breakdowns.”

The HCVs and rear axles are made in one area of the plant, while the engines are made in another. The four-cylinder and six-cylinder engine production is separated due to them being different sizes and having different cycle times – around 225 four-cylinder engines are made at Inönü every day, while just 45 six-cylinder engines are produced. However, both the nine-litre and 12.7-litre six-cylinder engines are made on the same line.”

As well as benefitting from the unusual production mix, the plant at Inönü is strategic in terms of location. “We’re a couple of hours away from our capital, Ankara, just one hour from Bursa, and two hours from Istanbul,” Hosver continues. “We don’t have the high costs involved in being in these locations, but can easily transfer things to and from them. Also, Eskisehir is a source for educated engineers and workforce, as well as an important base for joint projects with the universities. When you put this all together, Inönü is a very wise place to make investments, which is why we are spending more and expanding.”

In-house expertiseThe plant churned out around 6,000 HCVs in 2017, and Hosver hopes to achieve a 50% increase during 2018, with a target of 9,500 units set. “Currently we have stabilised at about 35 trucks per day, but we plan to go up to 45-ish by the year end,” he explains. “We have a really aggressive plan to go to 16,000 and 18,000 in a couple of years’ time. We are also increasing sales of our engines and rear axles for LCVs, mainly thanks to strong demand from the export market which increased by 50% between 2016 and 2017. In addition to that, spare part demand is climbing and is becoming a huge part of our business here.”

Ford Otosan exported $4.9 billion worth of vehicles in 2017, shipping a record 297,396 units to 89 countries. This accounted for 72% of Turkey’s total CV exports and 69% of Ford’s CV sales in the whole of Europe.

In order to meet rising demand and hit output targets, companies often outsource engineering or manufacturing, but that’s not the plan for Ford Otosan. On the contrary, Hosver is eager to outline the company’s strategy of maximising in-house production. “When you get a solution from a supplier it is introduced and then forgotten about,” he says. “But when we design and engineer something in-house, we integrate it, start using it for production, and then we keep revisiting it to see if we can make improvements. This gives us a great advantage in terms of costs over our competitors, and allows us to make consistent progress with our facilities.”

The strategy is extremely important in the HCV segment, he continues, as production numbers are far smaller than in the passenger vehicle segment. Therefore, paying for costly outsourced production work has a significant and continuous impact on profit margins.

As well as upping in-house capability, Hosver reveals that the company is investing in pilot projects to test the use of robots in certain production processes. “We are starting to use robots in some areas of production and doing case-by-case studies to see if it makes sense,” he says.

Change in the body and paintshopsOne example of testing robots and using in-house expertise is currently taking place in the bodyshop. It was established in 2017 and is therefore modern compared to some of the other areas of the plant, but work is still on-going, and parts of the bodyshop still house several inactive robots. “What we are doing here is programming them for welding operations,” explains Mehmet Ercan, Ford Otosan Inönü plant area senior manager. “After our shutdown period in August, the robots will be working and we station the human workers that are currently carrying out manual welds in other areas of the plant.”

The idea of programming robots in-house is not unique to the Inönü plant, but is also taking place at Ford Otosan’s Gölcük and Yeniköy plants, in which the Transit, Custom and Courier LCVs are made. By using this strategy, the company has managed to reduce investment costs in robots by around 60%.

Robots used in the new paintshop at Inönü, which like the bodyshop was established in 2017, are also being programmed in order to keep costs down. “We designed the entire paintshop in-house,” Ercan adds. “Due to the small production numbers, we haven’t introduced robot applications on the sealing process yet, but in the near future we probably will. However, the paint line is fully automatic. We have three paintshops in Turkey as Ford Otosan and this is the most automated one, with roughly 63% of processes completed by robots.”

Engineers at the plant are not only developing sophisticated software for robots, but have also drummed up ideas that have helped to increase production in other, less glamourous ways. At one point during HCV production, for example, the chassis needs to be flipped and rotated in order to go back down along a production line to be married to the cab. The company therefore integrated a unique belt mechanism that cradles and slowly rotates the giant chassis – an idea that was concocted and then quickly introduced in 2017.

Change is also taking place in the powertrain production area, with more robots being tested for certain processes. Yavuz Demir, powertrain manufacturing engineering senior manager at Inönü, highlights the introduction of two new projects, both of which are having a notable impact.

“The product development team have been looking at ways of reducing the weight of certain components in order to make the trucks more fuel efficient,” he states. “They have come up with a new design for the differential carrier in the centre section of the rear axle, so during the shutdown period this August, we will modify the carrier machining and other components in the centre section to carry out the new design.”

Ford Otosan makes around 15,000 trucks and tractors per year at its Inönü plant

Ford Otosan makes around 15,000 trucks and tractors per year at its Inönü plantAfter this, the powertrain team at Inönü will be preparing for the production of a new transmission. The company currently outsources its transmissions from ZF and Eaton, but, according to Demir, the plan “is to localise the product, so we will integrate a new assembly line soon. We will probably make the same number of transmissions as engines here, at 15,000 per year.”

Along with increasing efficiency, Hosver believes the use of in-house expertise can help Ford Otosan to better meet the varying demands of its customers. “There’s more of a push for tailormade production because the customer wants different wheel sizes and different suspension systems, for example,” he observes. “So this makes the production process very complex, but by using our own tailormade automated processes we can manage the demands accordingly.”

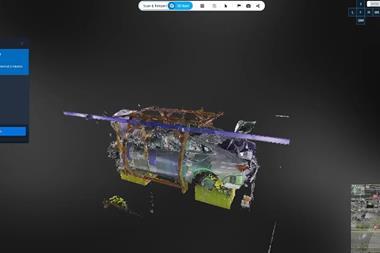

Linking to the futureLean manufacturing is another key phrase at Inönü. Although he thinks the plant has come a long way in recent years, Hosver is confident that many processes can be streamlined to improve efficiency even further. In some cases, he adds, certain process could become entirely redundant: “We are looking to make year-over-year efficiency improvements. To do that, we need to be getting rid of all non-value-add processes. We can use our experience for this up to a certain level, but after that we need automation and smart digitalisation to guide us.”

Connecting numerous systems is a notoriously difficult challenge in car manufacturing. This is because most plants use robots and other tools sourced from a variety of different companies. However, as Ford Otosan has been using its in-house programming strategy, Hosver thinks it has a head start. “We’re started making sure that our machines are all linked and talking to each other as well as the maintenance system,” he notes. “The next step will be to link the production system to customers, as customer demand could have a big impact on our manufacturing processes and applications.”

He refers to the trend of autonomous driving. Like many experts in the industry, Hosver believes that the HCV segment could become the first to adopt higher levels of autonomous driving technology. This is due to the fact that the routes these vehicles take are fixed and don’t often change, making it easier for computers to guide the trucks safely to their destination.

A truck chassis is flipped and rotated before it sits back down on a production line and is married to the cab

A truck chassis is flipped and rotated before it sits back down on a production line and is married to the cab“The drivers also have to operate the vehicles for very long periods of time,” he continues. “If we can leverage autonomous driving technology in the trucks then we can minimise the possibility of driver distraction, vastly enhancing safety while also improving driver comfort. It also allows the trucks to be driven even longer, which is important because every time they stop the companies that are using them are loosing money.”

As autonomous driving technology trickles into the truck segment, Hosver thinks that plants like Inönü will need to adapt, both in terms of layout and processes. More sensors will be added to the vehicles, which means production lines and component storage areas will change. And if these sensors start to drastically reduce the amount of road-traffic collisions, then more lightweight materials could be used in order to maximise fuel efficiency.

“If we really look into the future of autonomous driving then we may not even have a cab at all,” Hosver muses. “The implications that this would have on our plant is huge, but we’re already thinking of how we might best adjust to these kind of big changes, so we will be fully prepared when the time comes.”

This vision may be some 20 years away from coming to fruition, according to Greg Roger, policy analyst at the Eno Center for Transportation – a non-profit, independent think tank based in Washington, DC. “I think the technology to support autonomous long-haul trucking technology will approach maturity in the next five to ten years,” he commented in a recent PwC report. “However, we’re still ten to 20 years off from having fully driverless trucks from being a common sight on the roads. I think the fear of displacing human workers and the general public’s initial safety concerns will keep drivers in the trucks for at least another decade, maybe two, beyond that.”

As for the near future, Hosver describes several factors that will have a big impact on Inönü. “We have an increasing demand and so we are planning an increasing supply, expanding our production,” he emphasised. “Inönü is an area that Otosan will be willing to invest in, so our aim in the future is to expand our current business but also add additional businesses, not necessarily in truck, axle and engine assembly.”