At last week’s inaugural AMS livestream, Scania’s Mathias Wijkström was joined by ArcelorMittal’s Hugo Da Gama Campos to discuss making automotive production greener and how it is vital to put sustainability at the heart of the production system.

It’s no good investing in an environmentally friendly product and the odd sustainable production process if sustainability isn’t at the core of company culture. This was the message of Mathias Wijkström, head of global Scania production system office, at last week’s AMS Livestream Hour on Strategies for Greener Production.

“You maybe have a sustainability general, or you actually have a sustainability department at your company, but I think it is extremely, extremely important that initiatives are strategy-focused,” he said. “It has to become part of your DNA. It has to be part of your decision models; it has to be part of the methods and principles that guide the operational activities.”

If the whole company isn’t on the same page, it becomes impossible to make a real dent in the waste and emissions of the company. Wijkström explained the traditional way of dealing with waste – sending it off to landfill or incineration – was easy because it easily fits into a linear business model. A major goal for many OEMs is to switch to recyclable packaging, and if possible, to close the loop on the recycled material by using it to make new packaging.

Wijkström reckoned that if there is no joined-up sustainability drive within the company, it will be an uphill battle: “inside a company you have to go outside your functional responsibility and you end up with purchasing and then it becomes very important that you have a corporate strategy for those kinds of missions, because if you end up with two different functions with different KPIs, controlling where you’d like to go with sustainability and circular business, you will also fail.”

Top-down and bottom-up

Changing the company culture to one that is focussed on sustainability goes beyond just setting out some guidelines, it requires everyone to be on board, not least the executives at the very top. Being at a big, established company like Scania is both a big benefit and a big risk, as the company needs to balance having expertise in the processes and methods that are relevant for today and building relevant expertise for tomorrow, and not be afraid to get rid of parts of the business that have lost their relevance.

At the same time, it cannot neglect the established technology that is making the profit today. “It’s also about giving acknowledgement to the people who are working with the current production system and parts, but at the same time also get new knowledge about what could be relevant for the future,” Wijkström explained.

“As a company you have to [work with sustainability] if you want to stay relevant. Who would want to work for a company that does not have this in their decision models and doesn’t look at sustainability as important? If we don’t embrace this and we don’t understand it, we will not attract the young talent that we need to survive.”

An influx of fresh talent is vital, but the big risk for a big historic OEM is that the top and middle management, who have made a career in the world of yesterday, are reluctant to adapt to change. If they are not leading on innovative business models, the company will become a dinosaur, Wijkström reckons. Thankfully, Scania’s CEO Henrik Henriksson takes a keen interest in sustainability, according to Wijkström.

A pile of gold in the back of the truck

While company culture is essential, there is of course no substitute for investment in new technology and seeing tangible results. It’s all well and good to have long term goals like becoming CO2 neutral by 2050 but if you can’t back it up with short-term actions, it’s not worth anything.

As such, Scania has been investing in infrastructure and knowledge such as a battery assembly plant. Given how quicky the technology is evolving, that was not an obvious outcome two or three years ago. However, the amount of value tied up inside batteries became a deciding factor.

“Looking at the product we produce today, it’s about 98% recyclable, however it’s very low-value recyclable,” Wijkström said. “If you look into the future, with batteries becoming common for the heavy truck industry, we will end up with a pile of gold in the back of the truck. And this will of course be a value stream that will be very interesting to get hold of.”

Taking control of battery assembly means that it’s easier for Scania to ensure that the batteries can also be disassembled more easily. “If you can do that in a more cost-effective way than the competition, you will have an opportunity to make profit in that value stream as well,” he added.

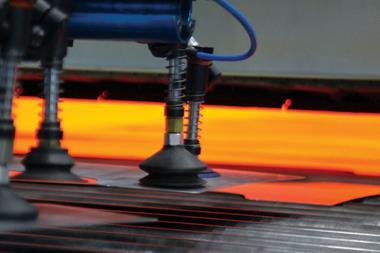

While OEMs need to move into entirely new areas, for material suppliers like ArcelorMittal, making production more sustainable is sometimes about fundamentally changing its processes. Steel is easily recyclable and as a result, 90% of the steel produced gets re-used. However, according to Hugo Da Gama Campos, who leads on sustainable development for flat products at ArcelorMittal Europe, the global demand for steel significantly outweighs the availability of scrap, which means that there will be a need for steel produced from iron ore into the next century.

Because of the sheer size of the global steel industry and because current steelmaking processes inherently have CO2 as a chemical by-product, the industry is responsible for around 8% of global CO2 emissions. Steelmaking needs to become a lot cleaner, then, but ArcelorMittal believes there are some realistic options to achieve carbon-neutral steel production.

Like a lot of companies, it is looking at switching its plants to renewable energy. It also sees an important role for hydrogen, regardless of whether it is produced using the carbon-neutral (when using green energy) electrolysis process or produced from natural gas, which inherently has CO2 as a by-product. Da Gama Campos explained that ArcelorMittal would be capable of using hydrogen to reduce the iron or to workable iron instead of carbon.

Using hydrogen produced using electrolysis would make the whole process carbon neutral, but even if hydrogen from natural gas is used, carbon capture technology can be used to neutralise that.

“This suite of technology is based on carbon capture utilisation, so we continue producing CO2, but then we capture that, and we can turn it into different products,” he explained. “[We have one particular technology where] we can capture CO2 and then, using a bio-fermentation process (it’s a similar process to making beer), we can transform that CO2 into ethanol. Then with that ethanol we can produce ethylenes for plastics or even biofuels.

Set your sights far and wide

Joined-up thinking about sustainability needs to extend outside the company, to partners and suppliers as well. ArcelorMittal’s Da Gama Campos said that one of the growing ways it is supporting vehicle OEMs is in closed-loop recycling, particularly using the scrap produced in parts manufacturing.

It is also looking beyond manufacturing. He explained: “Now the debate seems to be going a lot more to recovering vehicles at end of life. Europe is currently a net exporter of scrap and a lot of cars find themselves outside of Europe so there’s a lot of talk of closing that loop and keeping those cars within Europe so they can be used as scrap in steelmaking.”

A successful sustainability strategy takes both these strong relationships with existing suppliers, but also has an openness to partnerships with start-ups and specialised technology providers. “There are so many possibilities, and no-one knows exactly which way [technology] will go, so you have to work with partners and build new ways to collaborate,” Wijkström said.

“One example is that we were one of the first to invest in Northvolt, who are setting up a huge battery factory in the north of Sweden. On the other hand, we are also working with five companies who are more like solutions providers. You have to team up – You have to have the knowledge yourself, but you also have to be open to partnerships.”

Da Gama Campos concurred: “Like Matthias described, no company can do this on its own, so partnerships are essential – both in the sense of supply chain partnerships, but also partnerships with … the real technical expert companies. If I take one example, for carbon capture utilisation technology, we partnered with a company called LanzaTech. … Without partnerships like that we would be limiting our horizons.”

It is key for established companies to build and constantly re-evaluate their knowledge, processes and methods and get external help when required, and resist the inertia of big companies. Wijkström summed it up: “We are really good at building trucks. This is of course our strength, but we also have to look at the production system and … those competencies that are not relevant, we have to get rid of and we have to fill it up with new stuff. The companies that are able to do that – to build on what they have, their strength, and incorporate new strength, they will be the winners going forward.”

No comments yet