Dealing with pollution caused by waste plastic is high on the agenda for governments and environmental agencies. James Bakewell reports on how vehicle makers are making use of recycled plastics

As user of plastics on a colossal scale, the automotive industry was quick to respond to pressure from consumers, the government and the press to reduce the impact these materials are having on the environment, with many OEMs pledging to employ more recycled plastics in their vehicles. However, as was revealed at a conference organised by the British Plastics Federation (BPF) and held at Jaguar Land Rover (JLR)’s facilities in Castle Bromwich, UK, there are significant challenges associated with keeping these promises.

Television coverage such as the BBC’s Blue Planet natural history programme has highlighted the impact that the careless disposal of plastics is having on the world’s oceans, and there has since been a widescale shift in the public opinion of all plastic products.

In response to this, many OEMs have been quick to trumpet their green ambitions. For instance, Volvo announced that from 2025, at least 25% of the plastics used in its new vehicles will be made from recycled material. To demonstrate the feasibility of this ambition, the company unveiled a version of its XC60 T8 plug-in hybrid SUV that looked identical to the existing model, but had several of its plastic components replaced with equivalents containing recycled materials. The vehicle’s tunnel console was made from flax fibre and polypropylene (PP) derived from discarded fishing nets and maritime ropes, while on the floor, the carpet contained fibres made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET) bottles and a recycled cotton mix produced from clothing manufacturers’ offcuts.

The announcement was a statement of intent from Volvo, but also a rallying cry for its suppliers, the help of which it needs if it is to make its recycling goal a reality. It urged suppliers to the automotive industry to work more closely with carmakers to develop parts that are as sustainable as possible, particularly with regard to containing recycled plastics.

“It was very clever and worked well in terms of PR”, said Fabian Watelet, senior engineer sustainability, environmental legislation at JLR. “I’m sure they have plans, which is great for them. We have plans too.”

Reducing environmental impact

To its credit, JLR was somewhat ahead of the game. In March 2017 it revealed that the interior of its Velar luxury SUV could be outfitted with a blend of wool and suede cloth made from recycled plastic bottles from Danish textiles company Kvadrat, rather than leather.

However, JLR is taking a different approach to incorporating recycled plastics into its vehicles than that favoured by Volvo. For one thing, it will not set a target for the amount of recycled material it will use. Watelet says: “It’s not our main target. Our main target is to reduce the environmental impact of our vehicles.” For instance, any environmental benefits associated with using recycled plastic for a given part may be negated if that part weighed more than one made from virgin polymers.

JLR’s push to reduce the environmental impact of its vehicles is driven not just by public opinion, but also governmental regulation and policy. Currently, most global environmental legislation is based on increasing the fuel efficiency of vehicles and/or reducing their tailpipe emissions – the impact vehicles have on the environment while they are being used. Watelet believes that in the next 5-10 years these will change to encompass the entire lifecycle of a vehicle, so OEMs will be pressured to reduce the environmental impact of the manufacture and disposal of their cars, too.

Further, a boom in electric vehicles will see the revenue generated by governments from fuel tax drop significantly. Might they start taxing the materials used in a vehicle’s production instead?

As a result, JLR engineers have analysed the environmental impacts associated with the materials it uses. Watelet says: “Aluminium is the biggest impact we have, because we use a lot of it and it is very energy intensive to produce.” Steel has the second biggest impact, followed by plastics.

This determined, JLR is taking a four-pronged approach to reduce the environmental footprint of the plastics in its vehicles.

The first step is to determine how much recycled plastic it currently uses. “Believe it or not, but this is extremely challenging,” Watelet says. “The information we are getting from our supplier base, through the [International Material Data System] IMDS mostly, is not very detailed.” A percentage might be given or a box might be ticked, but a much more accurate overview is needed. Second, JLR will make recycled polymers the default choice for parts where all other factors – such as performance, weight and cost – are equal. Further, the OEM will work to develop new recycled grades. This won’t be easy, but JLR has a track record of success doing similar things with aluminium. Finally, Watelet says, “we need to recognise that for certain parts, there is no choice but to use virgin material.” In these instances, JLR will work to reduce the associated environmental impacts.

Much like Volvo, JLR needs the help of its suppliers to achieve these goals and Watelet laid out a number of its requirements. In the first instance, he said, “please don’t make any unsubstantiated environmental claims” and do share detailed life-cycle assessment (LCA) data with JLR. Be open to JLR’s LCA methodologies and support the carmaker in collecting accurate data. Further, provide detailed descriptions and use rates of recycled plastic in IMDS.[sam_ad id=17 codes=’true’]

In the longer term, Watelet suggested JLR’s suppliers should look to develop end-of-life vehicle shredding technologies – “the more materials can be sorted once they are shredded, the easier it will be to use recycled material” – and create new recycled grades of plastic.

Key, Watelet says, is that suppliers “refrain from the temptation to increase cost. At JLR it will be very difficult to consider using a material that is more expensive than virgin grades.”

Challenges facing suppliers

That might be a something of a sticking point. Peter Atterby is managing director of Luxus Polymers, which claims to be the UK’s largest independently owned producer of prime and recycled polymers. He says: “The typical opinion of recycled polymer is that it’s cheap, but [the costs associated with] collecting it from the curbside or post-industrial uses and bringing it back to a standard that is acceptable to the automotive industry means that its at least as expensive as a virgin product.”

Indeed, Atterby points out that in the drinks industry, where companies are keen to sell their environmental credentials to the consumer, recycled PET is now fetching a higher price than virgin grades.

Atterby says there is much the automotive industry could be doing to help its suppliers of recycled plastics. He points-out that buying a recycled product is not as simple as buying a prime product with defined specifications; there must be close cooperation and active discussion between the supplier and the OEM.The first step is to define the tonnage of material needed for given application – suppliers such as Luxus can then determine the amount of feedstock available and secure it for the lifetime of the product – and the performance requirements. In terms of performance a balance must be struck between making a product that is fit for purpose and one that is over engineered – increasing its price. Indeed, Atterby says that OEMs have put forward theoretical specifications that could not be achieved using even virgin materials.

It is important that as well as the technical team, the carmaker’s purchasing department is involved at this stage, reducing the likelihood of economic conflicts later in the process. Once the target volume, product and price have been established, research and development can begin. Or not. Atterby says that Luxus is not afraid to say ‘no’ if it believes that it can’t meet the criteria laid down by the OEM; “there’s no point in wasting everybody’s time”.

The automotive industry has to realistic in its expectations of what can be achieved using recycled materials. He recalls: “We matched a colour for an OEM against an original colour specification. We are now supplying five different versions of the same product. Why? Because we need five different textures for five different locations in the cabin. This is a recycled polymer, and the automotive industry wants it to be cheaper. There’s a bit of conflict there in how we square the circle.”Ultimately, Atterby would like to see OEMs setting up dedicated teams – comprising individuals from their sustainability, purchasing and engineering departments – “so we can all talk the same language. So we all know what the aims of a given project are.”

The pressures on OEMs to take greater responsibility for their impacts of the plastic they use on the environment aren’t going to disappear. It seems that having open lines of communication with their supplier base will be key if they are to be successful in relieving some of them.

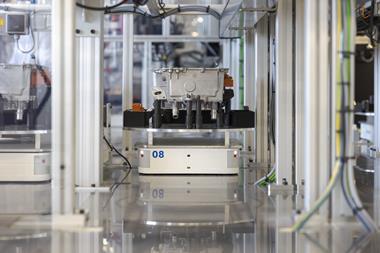

Modern vehicle interiors utilised a variety of plastics and textures, presenting a challenge when using recycled materials

Modern vehicle interiors utilised a variety of plastics and textures, presenting a challenge when using recycled materials