One for all integrators

How integrators and suppliers are adapting to ensure they keep up with the changing demands facing carmakers

As the automotive industry flattens in mature economies and emerging countries play catch up, global competition is forcing suppliers and integrators to adapt to constant change while performing flawlessly. And that’s true from concept to design and final vehicle production.

Price pressures and demands are greater than ever on suppliers, whether it’s integration in vehicle concept, design or build stages. The need to get to market, supplier collaboration and spot-on quality is pushing North America-based suppliers whose reach is increasingly global. “A major challenge facing integrators and suppliers is how quickly OEMs are ratcheting up technology and spreading it globally as fast as they can,” says John Haning, HMS Company’s Information Technology Manager. HMS was founded in 1960 by Hugh Sofy in Troy, Michigan. The company has been a quality integration partner and top-rated tool design supplier to General Motors Corporation for 33 years. It provides body-in-white processing and systems integration for every GM platform, current and future.

Integrators like HMS often work two to three years ahead of production. They are best placed to predict market changes, such as the shift away from larger trucks and cars to fuel-efficient vehicles sweeping across North America. Currently, they are working on design integration for GM products due for launch in 2012. “OEMs develop the vehicle manufacturing strategy. Suppliers then finalise the plan, execute the design and the build, and provide integration of tooling,” says Chris Buda, HMS Processing Group Manager and Haning’s partner. For a successful launch, change management and subsupplier coordination are critical components in the manufacturing process. “GM maintains control of the integration of all pre-production changes. Suppliers must function flawlessly throughout the entire integration and launch process,” says Buda. “GM controls changes in the process and execution and implementation has to be spot on.”

In an assembly plant shutdown situation, American Axle & Manufacturing Holdings takes planned, methodical steps to prepare for a closure. After all, it affects every facet of production from planning to integration to actual assembly and shipping. “The devil is in the detail,” says Abdallah Shanti, AAM’s Vice- President and CIO of IT, Electronic Product Integration. “We prepare for a good shutdown so we can have a good start up. In my ten years here, I don’t recall us ever having anything but a flawless launch after every shutdown. Our plans are very specific to the task that’s performed. Everyone collaborates on line. Even during a shutdown.”

The company produces axles, driveshafts and chassis components for most global automotive customers. General Motors owned the Axle group until 1994, when CEO Dick Dauch, a former GM plant manager, established the private company, retaining GM as its major customer. The company follows Dauch’s maxim that most management employees know by heart: “Develop the plan, work the plan and execute the plan. Build up. Build out. We bleed quality.”

The latest test for systems technology and integration came after an 87-day UAW strike against AAM this year (February to May) which crippled the US automotive industry and resulted in five AAM plants and dozens of North American assembly centres closing. Start-up after the strike, settled in late May, was smooth, officials recall. Factory information systems did their job.

AAM’s mathematics-based engineering processes incorporate exact logic, algorithms and production procedures to assure that AAM standards are met. “Integration challenges come when you are working with suppliers who are building the line for you,” says Shanti. “Testing and validation of those algorithms is done using advanced computer simulation. The results of those simulations correlate at 96 per cent confidence at this stage. The rest is a matter of fine-tuning on the physical line to achieve 100 per cent correlation.”

The technology enables its lean approach and global growth. In a new global product launch last year, AAM was building two lines for new products going to Brazil. One line was using a new supplier, the other an experienced one. The launch was flawless for both lines, according to Shanti, because the systems and steps were identical.

This year, AAM expects to complete 28 new launches, representing a 20 per cent increase in business, according to AAM officials. Even after a long strike, AAM leaders believe their robust processes and seamless systems assure their ability to execute flawlessly. “How do you beat the launch? You stay ahead of the launch. Once in it, you can’t fall down,” says Shanti

Rising quality expectations

Quality is becoming a moving target. Zero tolerance for defects at product launch is still desired, but the quality target keeps moving up in the design and pre-build stages. On the data side, HMS is a central player in the quality process. “Everyone in the supply chain gets information from the same source. Error is reduced dramatically because production data comes from the same system, and common technology tools are used,” says Buda. A key GM supplier communication and management software tool is called eBOP (electronic bill of process), a web-based Siemens PLM product from its Tecnomatix (CQ) suite. Updates are published to eBOP so the supply chain remains on the same page. Users can interact with and exchange 3D manufacturing data over the web to make informed decisions and respond to market demands quickly and with confidence.

Integrators have distinct responsibilities and a key one is to make sure the vehicle is designed for manufacturability, despite bumps along the way. “The biggest challenges come with late design changes that must be incorporated systematically,” says Buda. “As manufacturers go global, this is a big issue. You have to look at the grand scheme. It takes, for example, three weeks to go global and this makes it harder to do things quickly.” Some suppliers complain they lack internal controls, as they must follow OEM-directed strategies and technology requirements to the letter. Ironically, those requirements can stifle innovation in their shops.

Resistance to change

Supplier collaboration is both a blessing and a curse for those dealing with the realities of schedules, timing and the need to offer state of the art solutions. There is also a human resistance to continuous change when under pressure. “We have now reached a plateau where everyone is in a comfort zone. They understand PLM, for example, but we are not seeing the push to the next level – how to go faster, cheaper. Or they are still testing it and not sure the ROI is worth it,” says Haning. “The fact that everyone is on the same page can hurt innovation. It’s harder to push the envelope when multiple layers of collaboration and change exist.”

Collaboration is becoming the industry mantra in an attempt to produce cheaper and fuel-efficient vehicles that meet today’s consumer needs without sacrificing quality. It gets dicier as carmakers such as Chrysler outsource to suppliers to help build the entire vehicle from the ground up. That’s the case for the Jeep project, for example, which is produced by a consortium of suppliers and UAW-Chrysler workers in Chrysler’s Truck and Activity Vehicle Assembly Center in Toledo, Ohio. The US$2bn complex integrates suppliers, manufacturers and different management styles in a supplier park setting.

Virtual design and build

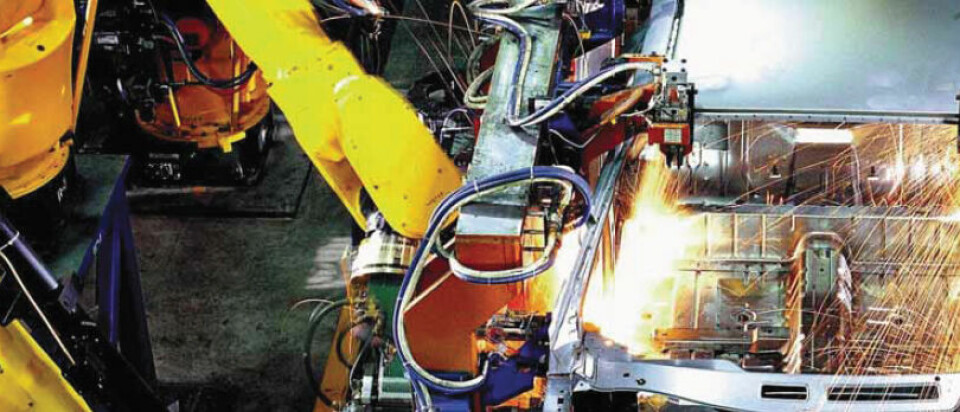

The need to speed products to market with flawless execution has led to increased virtual design and build processes for vehicles. That means the car is designed and built by the computer before workers and robots on the plant floor get to it. The software and hardware tools, too, are customer specific. “The trend is to accomplish physical builds from prototypes. The amount of physical building is reduced dramatically. This happens one year out and creates a trail of the entire process to assure data and tooling are sound and can be shared across the board,” says Buda.

Simulations are delivered to the plant floor and installed on the robot. For virtual vehicle builds, an integrator such as HMS uses an electronic mathematic model of the vehicle that is employed in crash-test simulations and other build configurations. On the software side, HMS, for example, follows OEM directives. It began using Autodesk programmes in 1983, at GM’s request. Autodesk is the parent company that produces AutoCAD, a GM requirement for computer-aided design. GM, for example, might use AutoCAD 2005 then wait for the 2008 release, but integrators must keep up with every revision.

Initiatives such as PLM are sweeping through manufacturing at a fast clip. PLM represents a US$24bn industry, according to consultant CIMdata, and the industry is positioned to grow to US$25bn by 2012. French producer Dassault Systèmes ranks first in PLM revenue, followed by Siemens PLM, PTC, SAP and Oracle. As PLM evolves globally, it becomes increasingly difficult to perform timely updates to the software solutions. “Today’s PLM software update implementations require a carefully planned execution because the updates now impact the OEM and its entire engineering supply chain globally. With the far-reaching integration of design software, these updates need to be completed on an almost simultaneous schedule,” says Haning.

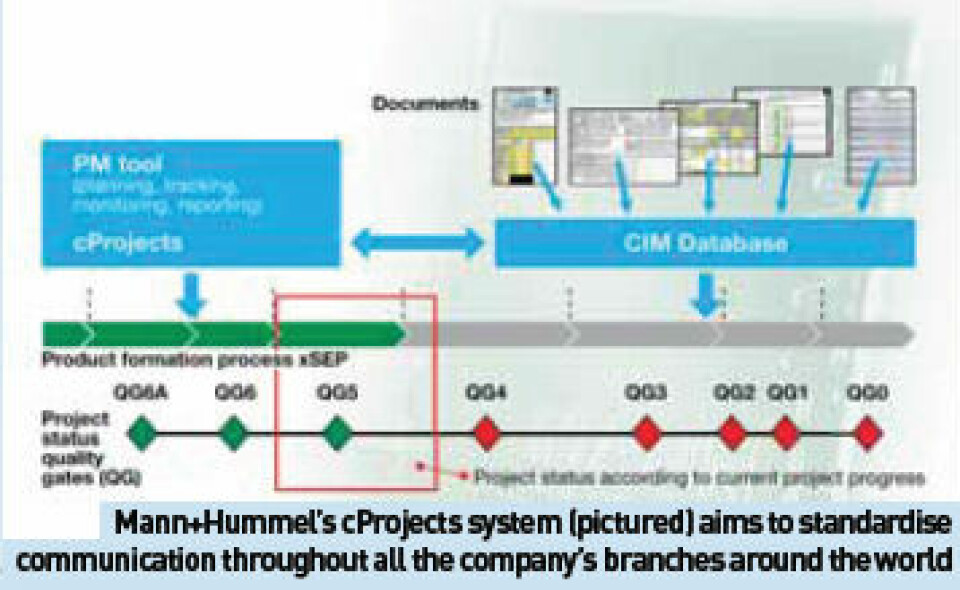

As business becomes increasingly global and complex, German fi ltration specialist Mann+Hummel USA found it needed common software-based project management tools with worldwide internet access. Important steps were being missed in the life of a project and data that was essential to sales, engineering and implementation teams in different global regions was not available.

M+H’s leadership issued a directive stating that the company needed a common communications basis for all global project work, a system that would tie together people and programs in 14 countries and many different languages.

In 2004, M+H developed its cProjects tracking system to adjust to a new way of doing business – and an expanding global presence. “The tool represents a standardised communication process and protocol for worldwide projects,” says Rick Wilson, who manages global programs for the company. The program is based on SAP’s cProjects software (‘c’ for collaboration) so all communication is stored on a global drive and provides internal internet access worldwide. SAP is a major automotive software provider similar to Microsoft and Oracle. M+H gathered representatives from 14 different countries to develop specific task lists and steps that track global projects from the business award to production launch stages.

Project teams set the minimum requirements needed and the task-orientated program now governs steps taken from start to completion, dates, time frames and who is responsible for completion. M+H specialises in air filters systems and components, intake manifolds, liquid filters, cabin filters and head covers with many integrated functions for most OEMs in automotive light-duty vehicles and heavy trucks. It has been steadily expanding its product development, testing and manufacturing operations in North America and internationally. The company’s cProjects involve five core team managers representing sales, design, engineering, purchasing, quality and manufacturing.

The core team members control the data flow and any changes that are input on web-based data forms. They work with the software and report changes and status into the database. The project end point is 90 days after start of production, when a project is passed on to production engineers and plant trackers. “We defined the core team as core members and extended team members. Other functional areas can bring information to the team and the database which is accessible by all teams worldwide,” says Wilson. Suppliers can feed into the system through the team members. “It’s a tool box for our global projects,” says John Baumann, Business Development Manager at M+H’s North American headquarters in Portage, Michigan.

According to SAP, cProjects’ strength is in project structuring, including project definition, phases, checklists and tasks. It includes roles-based resource management, flexible authorisation control and scheduling functionalities, together with broad project management and monitoring features. Before the system was adopted, each country used its own unique checklists and forms. The guidelines (and reports) were not serverbased, so weren’t accessible globally. Users, for example, did not know the steps they needed to follow before launching a project. Now there are links to key documents and other company information. The company also uses current software to support major OEM manufacturing projects, including CATIA, Unigraphics, CAD and IDEAS programs.

The company’s latest expansion is in South Korea. In September, M+H bought the Korean Dongwoo company, renamed M+H Dongwoo. It is also expanding its China operations this year. The company’s Michigan plant plays a major role in its growth strategy. The Portage facility, along with South Bend, began production of three new products in 2007 and expects four more program launches in 2008 for domestic and transplant OEMs.

The global footprint will only get deeper and wider. “Whether you supply a part, component or entire system, the key is offering it at a lower cost and supplying the (latest) technology,” says Baumann. “Our global footprint benefits us on many projects. An air cleaner system designed in Korea, for example, can be produced wherever needed – South America, North America or Europe. We match up with the customer footprint exactly.”

Getting it right from the start

There’s a maxim in the integration and controls world: “If it works early on, it works all the way through.” Rockwell Automation tries to make sure that maxim holds true across continents. Rockwell North America is a major global integrator, headquartered in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The company provides industrial automation power, control and information solutions to solve manufacturing problems. The company works with many major OEMs and keeps high walls between customer projects. Brands include Allen- Bradley and Rockwell Software.

“It’s a global environment. BRIC countries are where the bulk of new growth is coming from. OEMs in Germany, Japan and North America are increasingly developing markets around the world and need to be connected globally,” says Scott Howe, Director of Market Development for the automotive and tyre industries in Rockwell Automation’s Detroit, Michigan office. “You have to take a human resources mindset to deal with all of the global cultural issues in addition to the technology integration issues,” he says.

Rockwell integrators work with governance or controls committees at OEMs. “Suppliers constantly offer different solutions,” says Wayne Creech, Global Account Manager (Automotive Services Solutions), at Rockwell. “Along with the OEM, someone needs to answer the questions – does it work? What are the risks? Does it reduce costs?” A major change for the automotive industry is investing in virtual design. “We are already seeing the virtual design world as critical to helping carmakers get to market faster,” he says. “The software identifies potential issues early in the design process, significantly reducing debugging time and allowing for a more successful start up. Steps that were taking several months are now taking several weeks. “Hardware and software need to be carefully selected, noting details that include revision levels and interoperability requirements. OEMs rarely select all products from one vendor which draws more focus on this area of integration.” Before vehicles hit factories, intricate integration work is going on in the concept and planning stages. “We make changes during pre-design, when suppliers are not hired yet. This stage occurs before the program even rolls out,” says Creech.

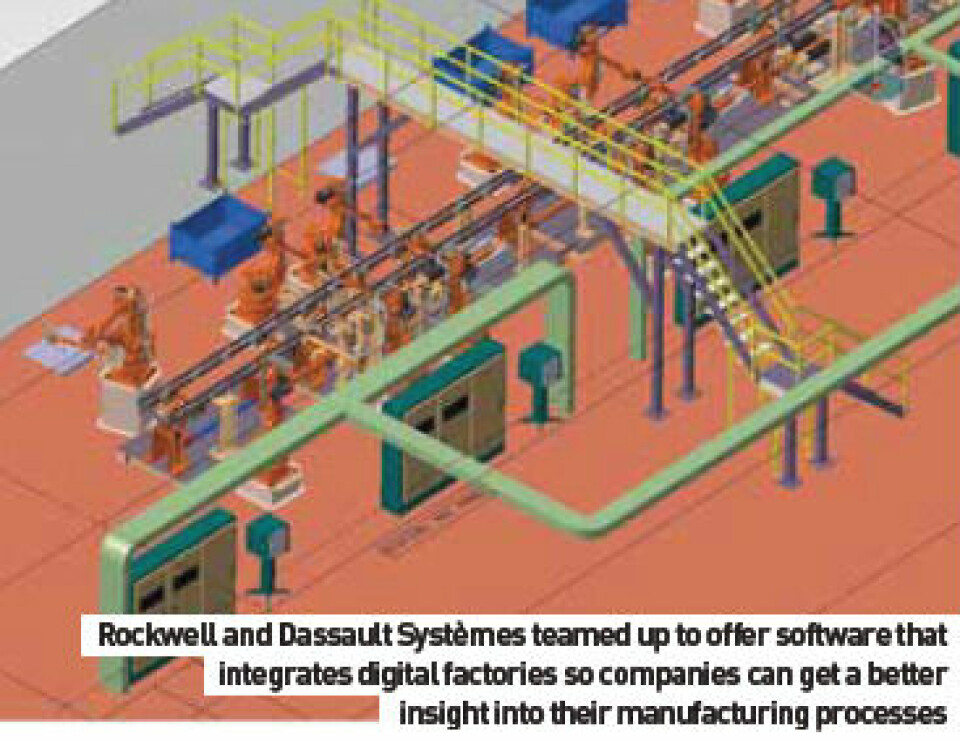

Early this year, Rockwell teamed up with Dassault Systèmes, a leader in 3D and PLM products, to offer software that integrates digital factories and gives companies insight into their manufacturing processes and business strategies. Two forward-thinking OEMs are using Rockwell to install a new manufacturing execution infrastructure within the next three years. Since this is business in process, Rockwell declined to name the carmakers. “The move to an information-enabled operation with tight integration to factory floor systems will help improve agility, productivity, reduce costs and assure regulatory compliance,” says Howe.

Coupled with the costs of replacing aged IT infrastructure and a reduction in some IT workforces, OEMs are now looking for more commercial off-the-shelf solutions for their manufacturing operations that are scalable, open and flexible to meet future needs. But the convergence of IT and factory systems has been slow in coming. Information to factory personnel is IT-enabled. But much of the activity still represents a convergence of two disparate worlds. “The IT area and shop environments are converging – many for the first time – so they can run product data,” says Howe. “It’s a steep investment for companies. Regardless of the solution, it takes time when deploying it across a large number of plants.”

• How to develop an integration process that incorporates the right checks and balances to ensure suppliers are following standards and specifications. This means they need to review the details of their design during the design, build and commissioning phases.

- Developing and releasing the appropriate level of standards specification early in the program timeline (before suppliers’ contracts are awarded) is a critical step in the integration management process.

- Accomplishing a lean launch with built-in first-time quality means taking as much variance out of the application and process before it hits the floor.

- In any integration setting, the software used depends on the carmaker’s business philosophy. GM specifies requirements down to the panel design.

- The challenge for the OEM is selecting a capable and flexible controls solution (future proof) early on that meets all requirements. That’s a difficult proposition since technology continues to evolve and manufacturing processes are being revamped often during any given programme life cycle.

- There must be many checks and balances in place to assure that potential problems are avoided before a product is used within a production environment. GM, for example, has corporate engineering staff constantly evaluating best practices within the industry to determine the best solution for their plant operations.

Source: Wayne Creech, Rockwell Automation

FactoryTalk – optimising manufacturing

Rockwell offers FactoryTalk Integrated Production and Performance Suite software, which is built on open industry standards. Its modular, scalable framework interfaces seamlessly with other options, which gives customers the choice of investing in a portion of it, as some OEMs are doing, or the entire suite. The program consists of multiple production disciplines that correspond with functional requirements common to most manufacturing enterprises, including a framework for integrating plant-floor data with business systems.

The virtual design and production environment will closely link product design to manufacturing and better serve manufacturers in addressing the needs of brand owners, tiered suppliers and machine builders. That solution will help enable collaborative mechanical and control design with bidirectional synchronisation. Manufacturers have told Rockwell that simulating the machine start-up in the virtual world allowed for it to happen four weeks faster than usual. FactoryTalk software can optimise design in a virtual world. Rockwell tried it with one line and saw it started up four weeks faster because debugging or fine-tuning worked quicker.

“It goes back to standards and specifications between disparate machinery which can be hard to link together. If you have standards up front, the architecture allows integration more flawlessly, which is critical,” says Howe. “Having good specifications and standards for this application layer, commonly known as the MES or manufacturing execution layer, is vital. This is where our FactoryTalk platform is targeted. “We are not a supplier of software in the virtual design space, like Dassault Systèmes, for example, but our FactoryTalk platform and integrated architecture have an object model that interfaces with virtual design suites like Delmia to facilitate.”

AVL’s growing ambitions

Major Tier One suppliers also act as integrators. Their main challenges include integrating their own shops and systems along with thousands of supplier and sub-supplier groups globally.

Austria-based AVL was founded by Helmut List in 1948. He saw the global footprint of the powertrain business at least ten years ago and made sure that AVL was well positioned to support the industry globally. AVL handles engineering projects for major OEMs and Tier One suppliers in cars and heavy-duty trucks.

“We work in the controls, engine design and development, powertrain and analysis areas connecting everyone together. It’s important that work is not done in silos and to be able to build across the globe. AVL is a leader in that,” says Ray Corbin, President of AVL Powertrain Engineering (PEI) in Plymouth, Michigan.

- Make sure you understand requirements, or you will start down a wrong path.

- Do a thorough engineering analysis of tools needed to do the job.

- With first-build prototypes, conduct analysis and understand problems pre-production – a failed engine bearing, a piston not properly sized or a combustion part not cut properly can have huge, expensive consequences.

- Understand system boundaries you are faced with so you’re not in a silo when in the design and development process.

- Cascade information and requirements through project teams comprised of everyone who touches the project, including sub suppliers.

Source: Ray Corbin, President, AVL PEI

Corbin oversees more than 220 people including designers, CAE engineers, software support engineers and engine development specialists. PEI also has a test facility for powertrain testing and vehicle emissions in Plymouth and Ann Arbor, Michigan. AVL, through PEI, is able to conduct projects from simple analysis of detailed aspects to total engine concept design and development.

In the past, most of the work the group did was on the instrumentation and engineering side, and it ended when production started. But that’s changing. AVL’s powertrain engineering group in Plymouth began as an engine combustion research facility and has expanded to undertake full powertrain functions, from concept to production. But now the company is faced with relentless pressure to do more, to expand its reach. As carmakers lean down, suppliers such as AVL are filling the integration and engineering role and expanding into production roles. “OEMs now ask us to do work all the way to production,” says Corbin. “At any one time there may be three or four competitors working simultaneously in our engineering facility.”

Part of AVL’s role is to supply automotive instrumentation and testing equipment to help OEMs pull development cycles as far back as possible. Work continues on a mathematics-based simultaneous engineering cycle so they can build products virtually and pre-production.

Preparing staff for global demands

“All our customers are very global and everyone is working 24 hours a day, seven days a week,” says Corbin. The human resource issue is – can people adjust to the pressures across continents? Globalisation means meetings and project reviews can happen any time of the day, offline and online. “This is now the norm, and our workforce is adapting to this global footprint,” says Corbin.

Shorter development cycles are also forcing suppliers to adjust rapidly. North American and global OEMs are looking for 36 months or less for a clean-sheet engine and powertrains, according to AVL experts. Reskinned or freshened vehicle projects are getting shorter too. In some parts, there’s talk of the two-year car or less, from concept. The faster-to-market environment demands that more planning and engineering work is done in a virtual world. “Customers, as well as AVL, are using advance simulation tools and techniques which incorporate design quality criteria which help to assure the standards are taken into account very early in the process,” says Corbin.

“When late changes are made it is usually very difficult to completely validate them and this can result in field issues.” Or it results in more late meetings (online and physical) with suppliers and OEMs – adding more complexity and expense to the process.