The Morgan Plus Six: a century in the making

Modern technology and traditional craftsmanship combine in Morgan’s most technologically advanced model to date

The Morgan Motor Company’s facility on Pickersleigh Road in Malvern is a car factory like no other. Founded in 1913, it’s a living, breathing piece of history – not just in its foundations, but in the traditional skills and techniques that are still practised here. But behind the unashamedly traditional exterior there’s a company that’s also keen to embrace modern production methods and processes.

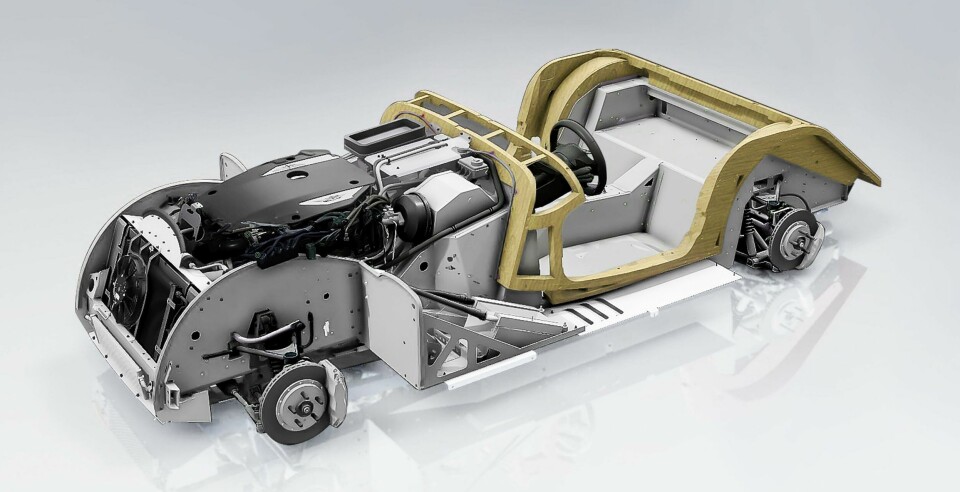

Nowhere is this unique blend of old and new better demonstrated than with the company’s latest flagship model, the Plus Six. Its body is little different in style or construction to the Morgan 4/4 that debuted in 1936, with aluminium panels draped over an ash frame. But underneath that sits a bonded and riveted aluminium platform that houses a turbocharged BMW straight six and an eight-speed ZF automatic transmission.

Design flexibility

This isn’t the first time that Morgan has used this sort of construction. The company’s first aluminium chassis arrived with the Aero 8 in 2000 and went on to underpin the reborn Plus 8 of 2012 (the model that this car effectively replaces). Nonetheless, the new CX platform marks a significant step on, as chief engineer John Beech explains: “We wanted to develop a platform that would be lightweight and provide good structural rigidity, while also offering plenty of design flexibility for future models. We’ve doubled the stiffness [compared to the Aero 8 chassis] but we’ve significantly reduced the material thickness – from 3 or 4mm down to 1.2mm in some places – which means it only weighs 97kg.”

There are no robots involved at any stage, but Beech maintains that manual production can match the quality of an automated process for a job like this

All the design work has been carried out in-house, but the production of the chassis is outsourced to Fablink in Northampton. The process starts with a series of flat aluminium sheets that are folded to create the chassis’ component parts (the only exceptions being two extruded sections that form the front bumper and part of the rear structure). Beech likens the resulting set of parts to a jigsaw puzzle – one that can be put together with a minimum of jigs and tools to reduce costs.

As with the Aero 8 platform, the bonding surfaces on the aluminium sheets are pre-treated with adhesive. They’re then assembled on a jig and baked at 180°C to create a single load-bearing structure. It’s this adhesive bonding process that gives the chassis its strength, he notes, although a small number of self-piercing rivets are used for location purposes.

There are no robots involved at any stage, but Beech maintains that manual production can match the quality of an automated process for a job like this: “As long as you have suitable process controls in place, there’s no difference between a part that’s been delivered by a human and one that’s delivered by a robot. We’ve been using this method for 20-odd years and we’ve never had a failure.”

Beech is no stranger to bonded aluminium construction. Prior to joining Morgan four years ago, he was the head of manufacturing engineering at Lotus Lightweight Structures. When he joined the Malvern company, part of his brief was to find potential improvements in the assembly and manufacturing processes for the new model. He’s also instituted a more methodical development approach, which sees the Plus Six become the first Morgan ever to be fully digitised in CAD. “We’ve put a lot more gate review phases in for this particular project,” he notes. “At each stage we’ve been applying a plan, do, check, act (PDCA) approach.”

Powertrain integration

The development process began with a set of technical requirements. It had been decided that the new car should use the same body in white structure and the same wheelbase as the outgoing Plus 8. This effectively defined the external boundaries for the design, while the BMW powertrain pre-determined much of the internal layout. The Morgan chassis engineers were essentially left to fill gap between the two, which meant that much of the geometry was already fixed.

Packaging was by no means an easy task. This is the first time that Morgan has used a straight six, which means it’s significantly longer than the V8s, V6s and inline fours found in previous models. To maintain favourable weight distribution, the team had set the target of packaging the entire engine behind the front axle. For ease of access they’d also been tasked with providing an extra 200mm of leg room and a 20mm increase in the size of the door apertures.

You can see the lengths that Beech and his colleagues have gone to when you look at the rolling chassis. The packaging is neat but dense and there’s been a conscious effort to eliminate external bracketry; a lot more components are now mounted direct to the chassis structure, he notes, which saves space, as well as reducing cost, mass and assembly time.

The BMW B58 is Morgan’s first turbocharged engine. This means that the engineers had to accommodate additional components on both the intake and exhaust sides, which adds to the challenge.

“We’re very pleased with the end result, but the packaging was an absolute nightmare at times,” Beech admits. “It’s a leaner, hotter-running engine than we’re used to, so there was a cooling challenge there, particularly when you consider that the grille area is quite a lot smaller on our cars [than the BMW applications].”

Wherever possible, Morgan has sought to employ BMW components elsewhere on the car

A thorough programme of CFD analysis was undertaken to ensure that the design could provide adequate air flow into and out of the vehicle. Particular attention was paid to the design of the undertray, to draw the air through the underside and past the exhaust system.

The powertrain development work was based at BMW’s test facility at Aschheim, near Munich. The Bavarian company appointed its own programme manager to oversee the project and worked with FEV to carry out calibration, testing and homologation. “BMW has been a great partner to us, we’ve been hand-in-hand the whole way through the development process,” notes Beech.

Spanish consultancy IDIADA has been another long-term partner of the project, tasked with putting the Plus Six through the European Community’s Small Series Type Approval. Ensuring emissions compliance has been vital to some of the country’s export markets and despite its generous 340PS power output, the Plus Six is one of the greenest Morgans yet, emitting just 180g/km of CO2.

Wherever possible, Morgan has sought to employ BMW components elsewhere on the car, although there were limits as to how far it was practical to go. “One of the reasons we haven’t taken that further is that BMW’s parts have to be more electrically-compliant than our vehicle needs to be at this time,” comments Beech. “The BMW rack, for instance, is an ASIL B design produced to ISO 26262, which means it’s got a lot of onboard intelligence. If we were to use those functions we would have needed to deploy extra management processes in the ECU and calibrate them, which would have incurred more development time and cost. Instead, we elected to find our own EPAS rack.”

Factory floor

Morgan’s roots stretch back to 1905 when company founder HFS Morgan set up a garage around a quarter of a mile away from the current factory. He produced his first car in 1909 and acquired the Pickersleigh Road site four years later. The earliest buildings on the site were completed in 1914 and they are still in use today.

Much of the current factory dates from the mid-1920s and the workshops are very much a product of their time, with brick walls and wrought iron roof trusses. They’re set out on a slight hill, which sees the chassis and powertrain components delivered to the top and the completed cars shipped out at the bottom. In the case of the Plus Six, this process takes around four weeks, while total production is approximately 800 cars a year. This figure has been fairly consistent for around a decade and the company has managed to whittle its legendary waiting list (once anything up to a decade) down to a matter of months.

Work begins in the chassis shop. Here, the bare chassis are fitted with their pipes and wiring, HVAC components and sound deadening. The engine, drivetrain and suspension are next, with one or two technicians floating between different cars. By the time the cars are wheeled down the ramp to the next workshop they are already essentially drivable, with a complete rolling chassis.

The body frames are constructed several buildings down the hill in the wood shop. They’re built using a series of standardised components – some milled from solid and others laminated from separate strips of ash – that are bonded together on a metal jig.

One tool in particular tends to draw visitors’ eyes. It’s a slab of oak – the sort of thing you might expect to see holding up the roof of an ancient village pub. Except here it’s used as a jig for the laminated strips of ash that make up the curve around the rear section of the frame. Nobody seems to know exactly how old it is, but the consensus is that it dates from the 1950s and every single traditional four-wheeled Morgan body since then has been made using the same tool, including the new Plus Six.

A separate workshop is devoted to production of the body panels. Most of these are shaped by hand on-site, starting with flat, uncut sheets of aluminium. The wings, however, are produced using the Superform process, which creates an A-grade surface that is essentially ready to paint straight out of the machine. Although recently toted by a number of other manufacturers as a fresh innovation, Morgan has been quietly working with this process for several decades.

Next, the completed body is carried up to the assembly shop, while the chassis is wheeled down to meet it. Again, it’s a small team of individuals who look after each car throughout this entire phase of the build, often floating between several highly skilled roles. It’s a noisy, frenetic environment with a constant banging of hammers and the smell of ash timber wafting through the air. Current Morgan CEO Steve Morris cut his teeth in this environment at the age of 16 and it’s hard to imagine it’s changed much since then.

Following the dry build, the panels are removed and sent for paint preparation. Once painted and reassembled, the car moves to the Trim Shop, where the interior and the final electrical items are fitted. Finally, each one is tested on the local roads and then sent for a pre-delivery inspection in a dedicated area with high tension lighting.

Mixing the new and the old

There’s a strong sense of tradition everywhere you go in the Morgan factory. Alongside the Plus Six, the workshops are currently still full of the traditional models, based on a steel ladder frame chassis that can trace its origins back to the 1930s. Times, however, are changing. Morgan has recently announced that production of these cars will cease in 2020 and that the Plus Six will be joined by a series of other models based on the CX platform.

The configurability that has been designed into the new platform should allow it to be used for a wide range of different models. In time, Beech explains, that could also include new powertrains: “We believe that this platform is flexible enough to take a number of different powertrain options. We don’t have any specific plans for those at the moment, but if the legislation required us to move towards electric or hybrid models we would have the flexibility to accommodate that on this platform.”

And therein lies the beauty of this company. Although parts of it haven’t changed greatly since the dawn of motoring, Morgan seems to have a talent for cherry picking new technology and combining that with traditional craftmanship. It’s a philosophy that’s stood the company in good stead for over a century. And you can bet it’ll still be going strong in another 100 years.