Dirty work in the clean-up

One of the biggest clean-up projects involving a redundant automotive manufacturing site in the United States – at least as far as its $120 million predicted cost is concerned – is currently taking place at the former General Motors Massena aluminium diecasting plant in New York state.

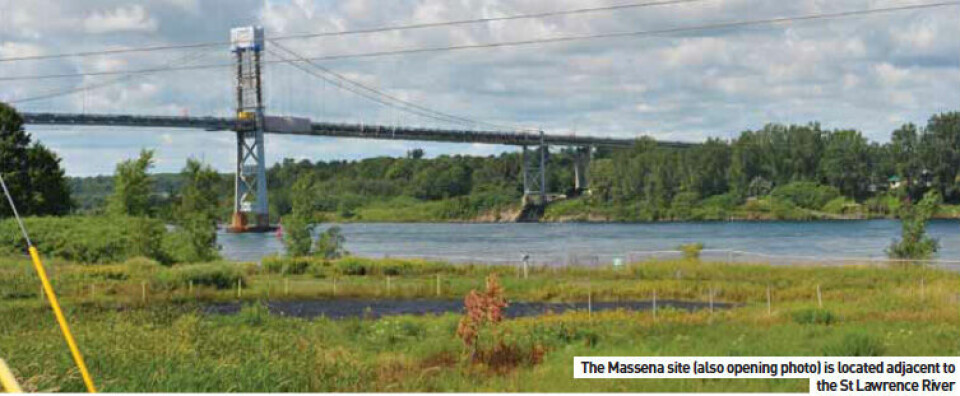

Located on the southern bank of the St Lawrence River, just across the water from Canada, the 270-acre site was in operation for 40 years until May 2009, when it because a victim of GM’s passage through bankruptcy. The site’s environmental issues all stem from the residues of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) that were a constituent of the hydraulic fluids used in production equipment until the early 1980s.

There are several discrete problem areas within the site, including a 12-acre industrial landfill, two further disposal areas and four industrial lagoons, as well as the St. Lawrence River and another watercourse to the Raquette River to the south. In addition, the PCBs and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) have contaminated the underlying groundwater. Aside from the proximity of two centres of population – the US town of Massena is seven miles away to the east, while the Canadian city of Cornwall, with 50,000 residents, is just two miles away across the St Lawrence. This site is especially sensitive because immediately to the east is a reservation for the indigenous St Regis Mohawk nation.

PCB sludge

As the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) noted in an analysis of the site published in 2011, PCB-laden sludge from one of the industrial lagoons and from a wastewater treatment plant had periodically been transported to the two disposal areas and to the landfill site. The latter was also used to store foundry sand, soil and concrete excavated during plant construction, and hosted diecasting machines and other solid industrial waste.

One of the two disposal areas, labelled ‘North’, contains contaminated construction debris, soil and tree stumps, while contaminated soil and sludge along with construction debris went into the other, called ‘East’. Neither of the two, nor the landfill, was lined.

The consequences of all this dumping makes for depressing reading. For instance, PCBs have been found in the groundwater, on- and off-site soils and sediments in the St. Lawrence and Raquette rivers. VOCs are also present in the groundwater, while phenols have been detected in lagoon sludges, as well as in the disposal areas. Fishing remains restricted by the New York State Department of Health. Environmental remediation did get under way while GM was still using the site, with the landfill being capped as far back as 1987 when it contained an estimated 297,000 tons of contaminated waste. Between then and its closure in 2009, the plant saw other clean-up activities which focussed on soils and riverbank sediments.

Taking charge

Since GM’s bankruptcy, clean-up responsibility has passed to an organisation called RACER, whose redevelopment manager, Bruce Rasher, confirms the long-term nature of the challenges. “Remediation at some sites will last for decades,” he says, adding that his organisation will retain responsibility even if ownership of a site passes over to a third party in the future. “Our mission is to integrate remediation with redevelopment,” he adds.

According to Brendan Mullen, RACER’s clean-up manager for New York state, the Massena schedule won’t be that long. He expects the ‘No Further Action’ notice from the EPA, which signals the completion of clean-up activities, to be given around 2015-16.

Actioning clean up

Based appropriately in Michigan, the traditional home of the US auto industry, the Revitalizing Auto Communities Environmental Response Trust (RACER) has responsibility for 89 former General Motors properties across the country, of which around 60 have required some environmental remediation.

After its bankruptcy, responsibility for cleaning up redundant sites passed to the formal successor of the ‘old GM’, the Motors Liquidation Corporation, set up a dedicated Environmental Response Trust. In March 2011 this was succeeded by RACER as part of the final resolution of the bankruptcy, with the brief to return each site to productive use.

RACER has funding of about $500 million and around 30 staff working to deliver action programmes set out by each of its four cleanup managers, They in turn take on geographical responsibility for: various areas, including: the Michigan area; New York state; Delaware; Louisiana; Massachusetts; Ohio; Pennsylvania; Virginia; Indiana; Illinois; Kansas; Missouri; Wisconsin; and New Jersey. RACER projects are supervised by the EPA (or by the state equivalent), and its actions are measured against six objectives when returning land to use:

- environmental remediation

- eventual sale price

- job-creation from the proposed re-use

- the reputation of any prospective purchaser

- local political and public opinion

- related benefits, including tangibles such as increasing tax revenue and intangibles, which include creating a ‘sense of renewal’.

As far as the environmental element is concerned, the specific objective is the issuing of a ‘No Further Action’ letter from the relevant regulator. The money and resources available to RACER are viewed with a somewhat jaundiced eye elsewhere in the US, including those impacted by former Chrysler production sites. About 14 Chrysler plants in the US have shut down over the past three years and, while some of the sites have been redeveloped, the majority remain disused. There is even a redundant GM plant in Jamesville, Wisconsin, which was shut before the bankruptcy and so is excluded from the RACER programme.

Among those focussing on the wider national problem is the Mayors Automotive Coalition (MAC), a pressure group formed by towns affected by automotive plant closures. Its policy advisor, Jon Wisbey, says it currently has around 20 active members, with three or more times as many taking an interest.

He says that when the former GM plants are included there are probably “over 50” larger sites looking for re-use. Include former supplier locations and the number moves up to hundreds, says Wisbey.

Though funding for environmental remediation schemes is available from the Federal government, particularly via a brownfield initiative administered by the EPA, Wisbey is downbeat about the prospects of significant extra funding to tackle the general issue of redundant sites. MAC is compiling what he describes as a toolkit of guidance and case study information on how to deal with the social, economic and environmental effects of automotive plant closures. It is scheduled for publication early this year.

Visible improvement

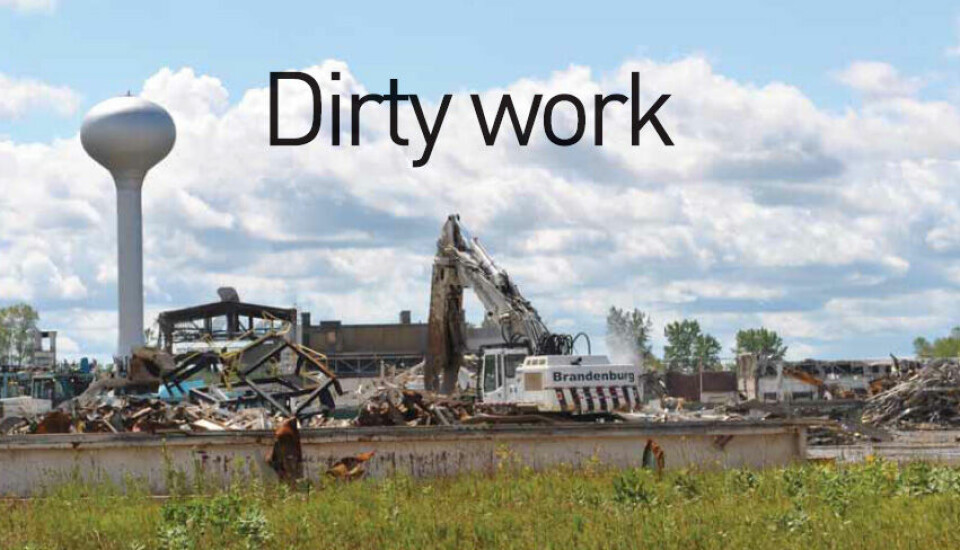

Back at General Motors’ Massena site, the end of 2011 saw work at the site taking place above and below ground, with the $5 million demolition of the main 855,000 sq. ft. production building, a predominantly steel structure. The current year will see removal of the reinforced concrete floor slab and a considerable amount of the subsoil beneath it. The slab covers 20 acres and varies from one to four feet in thickness - slightly less than 50% of it is contaminated. Unlike the not-yet visible soil, at least “we know where the contamination occurs,” notes RACER’s Brendan Mullen. He believes that some 14,000 cubic yards of subsoil is contaminated and so must be removed, though extensive exploratory testing has not completely defined the challenge. “We are expecting some surprises,” he says. Adding complexity is the network of tunnels beneath the slab, which acted as conduits for both air and oils, and which have a square cross-section measuring between six and eight feet.

The contamination, in of itself, does not make the task of breaking up the concrete or removing subsoil any different to a normal excavation, but it does create the need for strict segregation between contaminated and non-contaminated materials. This starts with the equipment used – there will be two, separate sets – and extends through transport to a licensed offsite repository. With a budget of $15 million, concrete and subsoil weighing some 63,000 tons will be moved, though with relatively little labour involved. At the peak of activity, Mullen expects about 20 contractor personnel to be on site, plus perhaps half as many specialist engineers. After the slab and subsoil, attention will turn to the lagoons and the landfill. Again, the processes are conventional in nature, even if meticulous in practice. The plan for the landfill is to dig up the contents and rebury them about 150ft away, this time cocooned in a protective membrane. Most of the material involved is no more exotic than sand; test probing has failed to reveal anything more solid, though there is the possibility of some old hardware. The lagoons will be filled with cement, which will soak up their content as it solidifies (again a tried and trusted technique) to allow subsequent retrieval and transport offsite.

Typical problems

Sometimes the potential environmental challenge from a closed site turns out to be a more straightforward business problem. The former Chrysler engine plant at Kenosha, Wisconsin, on the shore of Lake Michigan and about 45 miles north of Chicago, is one example.

It was shut in October 2010 but found to have no particularly noxious environmental legacy. The town’s mayor, Keith Bosman, says there are “the typical problems you might expect from a site that has been in use for over 100 years with little regulation covering the dumping of oil”, but adds that tackling its problems is well within the capabilities of established procedures.

Kenosha has been down this same route. Back in the late 1980s, its Chrysler assembly plant was shut, but the city authority acquired the site and invested some $18 million to turn it into a successful residential complex. Harbor Park is a now a picturesque lakeside location.

Though the former engine plant is shoehorned into a much less attractive built-up area in the centre of the city, this has not deterred the city authority from again taking an active role. It is seeking to avoid what the mayor regards as the twin evils of disuse, and of being stripped of reusable materials with no thought to redevelopment. The latter was a particular danger since one of the assembly facilities on the site was constructed just 12 years ago. Mayor Bosman says he waited no more than six months before he acted, especially since payments from new Chrysler to old Chrysler stopped in April 2011.

The cost of returning the engine site to a reusable state will be around $35 million, of which approximately $7 million has so far been found, says Bosman. He believes the balance can be raised without resorting to the commercial loans market, including a possible $10 million government grant available for renovating ‘abandoned’ sites. Ironically one condition of receiving that cash is the demolition of the existing buildings, even the relatively new one, in order to meet the definition of abandonment.